23 Feb After the Chase

Born with methamphetamine in his bloodstream, Roger Carver went on to become a child snowboarding prodigy before ultimately walking away from the sport in his prime

Roger Carver sometimes speaks like he’s writing a movie script. He refers to himself in the third person. He finishes a thought like he’s writing dialogue for Forrest Gump: “That’s all I have to say about that.” He muses over snowboarding with throwaway buzzwords that, given that he was born to a mother struggling with methamphetamine addiction, would make a studio exec’s hair stand on end. Habit. Chase. Addiction.

His younger days certainly had the cinematic elements—the prophetic surname of his adoptive parents, the backstory, the unlikely and meteoric success in professional snowboarding at such a young age. By 13, the energetic kid who began snowboarding at Sierra-at-Tahoe at age 5 had won 22 national championships, excelling at every discipline from racing events to halfpipe and slopestyle.

Roger Carver at age 10, courtesy photo

But Carver is now 29 years old. His time as one of snowboarding’s most talented young phenoms is long past. He abruptly walked away from the sport three years ago, still in his prime, leaving many wondering—including Carver himself—what could have been.

Other questions remain. What made him call it quits so suddenly? Were snowboarding fans robbed of seeing the full potential of Carver’s abilities on a board? Did the circumstances of his birth make him a better athlete? Or did his mother’s addiction hold him back from becoming the athlete he might otherwise have been?

Carver doesn’t love that the cliches are what people seem to remember most about him. But since his earliest years, people have been spellbound by Carver’s story.

When national sports magazine reporters began showing up on his doorstep in 2002, Carver was seven years into his professional snowboarding career. The journalists found a normal—though hyper and sometimes trouble-making—kid who sang to himself as he ripped down the slopes.

Coaches, journalists and fellow competitors were sure they were witnessing the making of a snowboarding legend—the early years of a dominant force in the sport.

It was never that simple, though. His career was many things: triumphant, heart-breaking, complicated, fun. But now, without a board under his feet, the questions and complications are different. As Carver says, “I think we’ve gone to a whole ‘nother chapter in my life.”

Carver at age 10, courtesy photo

Little Ripper

Carver’s snowboarding coach, Kyle P. Frankland, stood in a Mammoth Lakes hotel lobby the day before a national championship race in the late 1990s. Cameron Beck, an 18-year-old snowboarder, appeared suddenly, nearly colliding with Frankland. Beck grabbed the coach. “He’s nuts!” he shouted, only half joking. “Get him back on his meds!”

A boy nearly half Beck’s size skidded around the corner at top speed, wielding a pool cue. He was laughing maniacally.

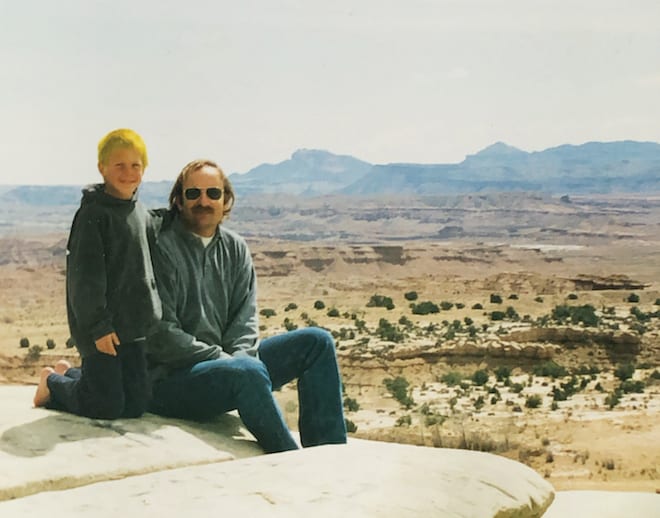

Carver with his adoptive father, Dave, while road tripping across the West, courtesy photo

As a child, Carver had mountains of energy. When it wasn’t being channelled into terrorizing kids more than twice his age, it all went into snowboarding.

The next morning at the top of the slope, he stared hard at the closest gate as Frankland explained the race course to him. Sometimes he would forget there was another gate ahead of the one directly in front of him and crash, shooting violently off course.

“But 90 percent of the time, he’d rip through those courses like mad,” says Frankland.

It was hard to miss the tiny snowboarder in those days, with his hair, dyed egg-yolk yellow, hanging out of his helmet. He often wore tie-dye, and was virtually always the kid snowboarding faster and boosting higher than anybody else.

“There was no other youth snowboarder who had as much success as Roger, except for maybe Shaun White,” says Mick Dierdorff, an Olympic snowboard cross racer who grew up competing alongside Carver. “Roger won everything as a kid.”

From that early age, Carver was after the feeling that only snowboarding gave him.

“It was a chase,” he says. “It was like one of those little cat toys hooked on that little string on a stick—chasing it. It was an addiction. This feeling of getting into the start gate—and your heart, just shutting everything down on you out of excitement.”

Carver, at age 10, stands atop the podium during the 2000 Junior Nationals at Waterville Valley, New Hampshire, along with his K2 teammate, Ross Baker

Rocky Beginnings

Despite the circumstances of his birth, Carver has only ever known a loving, supportive family.

At just 10 days old he was handed over to Terrie and Dave Carver, who lived near Placerville, after methamphetamine was found in his bloodstream—the result of an experimental two-week period during which El Dorado County tested every newborn for drugs. The positive test allowed Child Protective Services to monitor his mother, who was given back her child after he had lived with the Carvers for six months. Three months later, however, Child Protective Services returned to find the infant malnourished, and he was promptly returned to the Carvers, who adopted him.

For years, to deal with attention and hyperactivity issues, Carver took medication—little blue Adderall pills during the day and white clonidine pills at night. Outside Magazine and Sports Illustrated reported that he’d probably have to stop taking his meds, which contained amphetamines that are banned by the International Olympic Committee, if he were ever to compete in the Olympics.

Missing a dose—which he often did, because nausea and sluggishness often came with the pills—made him a different kid.

“Instead of going 100 miles an hour, he’s going 300. Then it’s Tasmanian devil time,” Trevor Brown, Carver’s longtime coach at Heavenly, told Outside in 2002.

Carver is more concise: “I was a little shit.”

The explosive energy stuck around through puberty, but with a 6-inch growth spurt and growing pains in his knees came a newfound mental focus that allowed him to stop taking the pills. He buckled down in high school, took classes at the local college and graduated a year early. From that point on, it was all snowboarding, all the time.

“I had to kind of make a choice,” Carver says. “At the level I was at, it would be too demanding for me to be successful in the sport and [continue to] do school, for me personally. I had to give one or the other my all.”

Carving Out a Career

In Carver’s eyes, his “overcoming the odds” narrative ended the first few years of high school. He wanted people to look at him and see him for his talents, for what he’d accomplished, separately from the obstacles he’d overcome.

He carried his childhood success through his teenage years, sweeping the USASA National Championships on numerous occasions before competing in his first World Cup snowboard cross race in 2009.

While performing well in NorAm Cup events, Carver spent a few years as a “bubble boy” on the edge of the World Cup circuit rankings. But by 2014 he’d distinguished himself enough that he was picked for the U.S. Snowboarding Team’s snowboard cross development group.

A year later, after finishing 12th in La Molina, Spain, Carver received a nomination to the U.S. Snowboard B Team.

This was not a slow or unusual career path for a competitive snowboarder. Dierdorff, who had grown up racing nationally alongside Carver, was also on the B Team in 2015, just a few breakthrough results away from a bump to the coveted A Team.

“A lot of people start seeing success [in snowboard cross] in their mid-20s to 30-ish,” says Dierdorff, who was an Olympian in 2018 and is on track to compete in the 2022 Winter Games in Beijing.

It surprised Dierdorff as much as anyone, then, when Carver quietly hung up his snowboard and went home to Placerville that same year, quitting competitive snowboarding for good.

Carver was 26—not old by any stretch of the imagination, certainly not by snowboard cross standards.

Walking Away

After the summer, the U.S. Snowboard Team was waiting on a response to their nomination. But Carver did not renew his contract with the International Snowboard Training Center.

“If I look back, I have no regrets on what I did or how I did or how I did it, you know?” he says, pausing. “But it’s something you think about a lot.”

Roger Carver at Sierra-at-Tahoe in January 2020, photo by Brian Walker

A few months before he retired, Carver started wondering if he was paying for his happiness (he estimates that one season of competition cost him $40,000). Competing on the World Cup as a member of the B Team—which, unlike the A Team, is unfunded—simply having the money to travel to every competition to accumulate circuit points is crucial.

Lacking funds, Carver had to pick and choose his events. At which race was he most likely to excel? Which would give him the most points? Provide the most exposure? He skipped the ones that didn’t check all the boxes and saved his money for the ones that did.

During the offseason, he and his teammates worked part-time jobs as waiters or carpenters in between intense training sessions. It was an exhausting lifestyle that, along with the monetary challenges, eventually wore Carver down.

“The reality is that, I think, if Roger had had more money backing him, we probably wouldn’t be talking about it right now,” says Frankland. “Because you would be writing an article about an Olympian who’s still an Olympian.”

Instead, with no health insurance or a conventional job, Carver felt like he had no cushion to fall back on, and he walked away from the sport.

“It was just time for me,” he says. “You can’t look back on it. You can’t regret it. Each person is different, you know? Each person can handle a certain amount of stress and everybody’s situation is different. And I feel like I went until I was comfortable to not go anymore.”

Still, Carver had a tough time accepting his decision. It wasn’t the first time he’d left the sport (he took a two-year break from 2011 to 2013), but this time, as soon as he landed on the choice, he knew it was for good.

“It was like breaking up with your girlfriend,” he says. Then he laughs. “I don’t know. Maybe. But way worse, I guess.”

For the first time since childhood, the answer to the question, “What’s next?” wasn’t snowboarding.

The Power of Nurture

In 2003, Ed McClain, one of Carver’s coaches at Heavenly, was asked by Sports Illustrated if the young champion was a better snowboarder for his drug exposure.

“We’ll never know that,” McClain said. “Maybe he would have been even better without it.”

Fifteen years later, it’s impossible to close the case file on that question. But did Carver have to quit snowboarding because that part of his past finally caught up to him? The short answer is, unequivocally, no.

With drug-exposed children, scientists have learned that in whatever battle “nature” and “nurture” wage in the brain, nurture matters far more, and can in fact negate the effect of nature.

“Whether or not there are lasting effects [from the drug] is going to be probably due more to environmental influences than anything that the drug has done,” says Dr. Barry Lester, a professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at Brown University.

Because Carver was adopted quickly into a loving family, he had a stable environment on which to build his life. He had the strong emotional attachments that Lester calls “protective factors” to his parents, who unconditionally supported him through his career, as well as the burgeoning snowboarding world, his teammates and his coaches. Without that, Carver admits that he could easily have taken a different path in life.

“Absolutely… Let’s say my upbringing was a little bit different, right? Let’s say I wasn’t given opportunities, right? I find other things to do,” he says. “I start hanging out with the wrong crowd. I start doing drugs, I start, you know, boom—I get hooked, even a hundred times easier than the normal person, because [I’ve already been] exposed.”

Civilian Life

After hanging up his snowboard, Carver landed back in Placerville and began picking up work where he could. He got a job at Blue Shield of California, where he’s a learning developer, coaching employees on how to machete their way through the jungle of insurance options. The company has become a kind of family to him, and there’s a smile in his voice when he talks about his work. He wouldn’t go back to competing in snowboard cross now, but he still thinks about what could have been.

Annie, Carver’s Jack Russell terrier, enjoys a ride in her owner’s rock crawler, courtesy photo

He’s read up on professional athletes and military personnel adjusting back to civilian life. His research revealed that they sometimes have trouble making the jump, because they can’t live without the adrenaline the job gave them for so many years. “You know, there’s still nothing like that feeling,” he says.

Carver still snowboards for the pure love of the sport. When time allows, he’ll drive up to Kirkwood or Sierra-at-Tahoe, where the mountains are clogged with riders, all of whom are slower than him. He still has a tendency to “send it” in life, having never lost that competitive edge. But that edge rarely comes out on the slopes anymore.

“It’s not the same,” Carver says, but not unhappily. “I allow myself to not have to be the best. I don’t have to push myself in the same way. It’s been nice to focus on not having to do the coolest trick or be the fastest person—just going out and doing whatever you feel like doing.”

Carver is adjusting to life after competitive snowboarding. His work is his passion, but he’s still looking for a sport that lights him up like his former profession. He fixes up trucks. He bikes and rides motorcycles. He paddleboards and wakeboards. He goes crabbing. Sometimes his Jack Russell terrier goes with him.

“I’m exploring life,” Carver says.

But snowboarding at an elite level is hard to replace entirely. Finding something that gives him that same elixir of adrenaline, challenge and competitive focus—the mixture that made up so much of his unique story—is now the next challenge in this chapter of Roger Carver’s story.

“I can’t even explain it,” he says. “There’s nothing like it. There’s nothing like waking up at 5:30 in the morning, getting yourself on a chairlift when it’s negative-20 degrees out and then you’re hitting 100-foot jumps…

“I’m still trying to find parts of that. You know, it’s still a habit in Roger’s blood.”

AJ McDougall is a writer and researcher based out of Nevada and New York. She’s currently working toward an English degree at Columbia University, but comes home to Lake Tahoe whenever she can to ski and hike.

No Comments