29 Nov Road Trippin’ to Las Vegas’ Outer Orbit

Exploring off-the-wall art and winter adventures on the long drive from Tahoe to Southern Nevada

Las Vegas is like Coke versus Pepsi. Visit the city a couple of times, and your opinion of it will likely swing hard either way.

Love it or hate it, the draw of Nevada’s most populous metropolis can’t be denied. Concerts, conferences, gambling and sporting events attract over 3 million visitors to the city every year.

Most people come for the casinos on the Strip and leave with an impression defined by how much entertainment bang they got for their buck. Which often comes down to luck or good timing, as the odds of finding a fair deal for anything on the Strip are not high.

Fred Bervoets’ Tribute to Shorty Harris at the Goldwell Open Air Museum. The prospector honors the first man to find gold in the area, and the penguin reflects the artist feeling out of place in the desert

But while the Strip might be the blazing sun that makes the city the brightest in the world from space, there’s much more to explore in the greater Las Vegas galaxy. And to no surprise, the farther from the neon lights, the easier it is to avoid the tourist tax that often leaves visitors unsatisfied.

Embarking on a midwinter road trip is one of the best ways to unlock the oddities and adventures found in Las Vegas’ outer orbit. From surreal art and ghost towns to wild wilderness experiences, several unique points of interest make the drive from Lake Tahoe worthwhile.

Winter is also a great time to visit Las Vegas because there are no 100-degree days, and December–February is the slow season on the Strip. If you coordinate your road trip with a concert or show, you could score some of the best deals of the year on tickets and hotels.

So gas up, buckle up and cue up your favorite driving playlist. We’re hittin’ the highway and heading south through the heart of Nevada. First stop: a forest like nothing in the Sierra.

From Bighorns to Boomtowns

Las Vegas is about a 500-mile drive from Tahoe. The fastest route, which takes around seven and a half hours with no stops, travels through Reno, Yerington, Tonopah and Beatty as it zigzags to the southeast. Most of the route follows U.S. Highway 95, a well-maintained two-lane road with a speed limit of 75 miles per hour. As long as you’re comfortable passing in the opposing lane, the drive is relatively cruisy, especially during the day. Between the rugged desert views and random roadside eye candy, the miles tick by quickly.

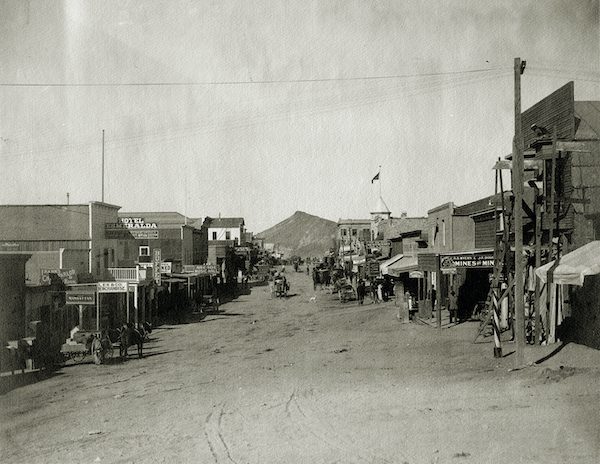

Goldfield, Nevada, in its heyday at the turn of the twentieth century, photo courtesy University of Nevada, Reno

The first highlight of the drive is the chance to see desert bighorn sheep near Walker Lake. Look for sheep in the broken cliff bands west of the highway. Just past the lake is Hawthorne, home of the U.S. Army’s largest ammunition depot, with nearly 2,500 bunkers built for storing a stockpile of bullets and bombs.

The next 100 miles are fairly uneventful—until you reach Goldfield. For Nevada history buffs and fans of weird art, this is where the journey starts to get interesting.

Goldfield is the quintessential mining boomtown. After gold was discovered nearby in 1902, the town’s population ballooned to 20,000 by 1906, briefly making it the largest city in the state. Goldfield’s glory days were short-lived, however. Most of the mines went bust by 1910, and a massive fire sparked by an explosion at a moonshine still destroyed most of the town in 1923.

Fewer than 200 people live in Goldfield these days, and only a few historic buildings remain. Nonetheless, this “living ghost town” still has zany character thanks to a legacy of creative residents.

The International Car Forest of the Last Church is open 24/7

Going for the Guinness

Goldfield’s eccentric flair is on full display at the International Car Forest of the Last Church, a quasi-sculpture garden made of graffiti-adorned junked vehicles about a half mile off the highway on the southern edge of town.

The car forest was the brainchild of Michael “Mark” Rippie, a Goldfield resident who owned 80 acres of land and a few dozen dead cars. In 2002, Rippie dug a hole with a backhoe, dropped in a car upright and became fixated on earning a Guinness World Record for the most upturned cars used in an artwork. Guinness didn’t recognize a record in that category (and still doesn’t), but Rippie hoped they would if he planted more cars than the 39 used in Nebraska’s “Carhenge,” a tribute to England’s famed Stonehenge.

Work on the car forest gained steam in 2004 when Reno artist Chad Sorg began helping Rippie. Sorg brought a much-needed creative vision to the project and painted crazy art on the planted vehicles.

The pair spent the next seven years half-burying dozens of cars, buses and trucks at odd angles in and around a small valley on Rippie’s property. Viewing the forest as an “artist’s playground,” they allowed the public to visit for free and welcomed graffiti artists to tag up the vehicles.

After successfully planting more cars than Carhenge in 2011, Rippie and Sorg had a falling out. Rippie then ran into legal trouble in 2013, which halted work on the property until he sold it to another Goldfield resident a few years later. The new owner believes in preserving the art installation and started a nonprofit in 2020 to help with property maintenance. The car forest remains open around the clock, and the owner encourages visitors to leave their mark on it.

“We go out to the car forest every week and find new art,” says Richard Dizmang, the site manager, secretary and treasurer. “Our motto is, ‘Bring paint, make art.’”

At the International Car Forest of the Last Church, visitors are encouraged to bring paint and add their art to the installation

The nonprofit group has resumed planting vehicles in the forest—though they are not interested in your trashed Toyota Corolla.

“We turn away most cars that are offered to us,” says Dizmang. “We’re only looking for vehicles that have a large surface that can be used as an art canvas.”

Rippie, who died in 2023, asked to be laid to rest in the forest.

“We went through the process of making a portion of the property a legal private cemetery so he could be buried there,” says Dizmang.

It was a fitting honor as Rippie viewed the car forest as a sanctuary and named it The Last Church in reference to his own thoughts on religion.

“I came up with The Last Church as a representation of the last church being inside each of us,” Rippie told High Country News in 2013. “Meaning that we should pass knowledge to each other from one heart to another about two things: unconditional love and compassion.”

The ruins of Rhyolite include the three-story facade of the Cook Bank building

From Gold Fever to Ghost Town

Goldfield is about a two-hour drive from the outskirts of Las Vegas, and an hour from a quirky town named Beatty that’s a gateway to Death Valley National Park—and home to more desert curiosities worth a quick detour.

Five miles outside Beatty sit the last remains of Rhyolite, another turn-of-the-twentieth-century mining boomtown. Gold was discovered near Rhyolite in 1904, and just like Goldfield, it transformed from a dusty mining camp to a bustling town. A three-story bank building with marble floors sprang up alongside hotels and an opera house as investors clamored to get rich off what was rumored to be one of Nevada’s biggest gold strikes to date.

But the paint had barely dried on the buildings when the mines began faltering. By 1907, Rhyolite’s boom was over, with more people leaving than arriving at the brand-new train station. The town limped along for a few more years until the last major mine closed in 1911. By 1920, Rhyolite was all but deserted, beginning its second life as one of Nevada’s most famous ghost towns.

The towering stone facade of the bank building, the still-intact train depot and a restored house made of 50,000 glass bottles are the most notable remaining structures. The bottle house was built in 1906 by a local stonemason named Tom Kelly, who paid kids 10 cents a wheelbarrow to bring him bottles from local saloons. In an area devoid of trees, bottles were a cheaper building material than wood.

The Bureau of Land Management now manages the historic townsite, where most of the structures are fenced off at night to avoid vandalism and open for closer inspection during the day.

From Barren Desert to Creative Garden

A Belgian sculptor named Albert Szukalski visited Rhyolite in 1984 and was so moved by the desolate majesty of the surrounding desert that he decided to stay and produce a new art piece. His sculpture, titled The Last Supper, features 13 life-sized ghost figures posed like Christ and his disciples in Leonardo da Vinci’s painting of the same name.

The Goldwell Open Air Museum’s signature sculpture, Albert Szukalski’s The Last Supper

To make the shrouded figures, Szukalski wrapped live models in burlap fabric soaked in wet plaster. When the plaster set, the models slipped out of the rigid forms, which were then sprayed with fiberglass for weatherproofing.

The sculpture was relocated the following year to a 15-acre private property a half mile down the road owned by one of Szukalski’s patrons. Six years later, Szukalski returned to Beatty and invited three other well-known Belgian sculptors to come and make art. By 1994, the artists had completed six pieces, turning the property into an unconventional desert sculpture garden.

Before Szukalski died in 2000, he asked artists Charles Morgan and Susan Hackett-Morgan to take over management of the sculpture garden. The Morgans subsequently founded a nonprofit organization in 2001 called the Goldwell Open Air Museum, which became the official name of the property.

Albert Szukalski’s Ghost Rider is one of the featured sculptures at the Goldwell Open Air Museum in Beatty, Nevada

A few new artworks have been added to the museum in recent years, though the sculptures by Szukalski and the Belgian artists remain the centerpieces. Beyond the eerie Last Supper installation, other prominent sculptures from the original collection include a 25-foot-tall female figure made of cinder blocks and an equally tall metal silhouette of a prospector with a penguin.

“I learned from Susan Hackett-Morgan to be very particular about what sculptures we get involved with,” says museum president Michelle Graves. “New pieces have to be inspired by the desert and in line with our mission. We get emails constantly about leftover sculptures from Burning Man, but we’re usually not interested.”

The Goldwell museum is free and open 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Just remember to bring a flashlight if visiting at night.

“When I go to Goldwell at night, I always get a sense of serenity,” says Graves. “It’s so quiet out there, and we’re dedicated to protecting the dark skies so there are no lights anywhere.”

From Drones to Dropping In

Beatty is 120 miles from Las Vegas. The next stretch of highway passes Creech Air Force Base, a heavily secured facility that serves as the command center for the U.S. Air Force’s unmanned aircraft programs. Airmen stationed at this base control squadrons of drones used for reconnaissance, surveillance and attack operations overseas.

While cruising past Creech, look to the southwest. The broad expanse of the Spring Mountains will soon come into view, including Mount Charleston, the 11,916-foot-high point of the range. Las Vegas is not a well-known ski destination, but when the snow conditions line up, there are undeniably fun turns to be had in the Spring Mountains backcountry as well as a ski resort called Lee Canyon.

Allison Lightcap slices into a sweet slope in the Spring Mountains of Southern Nevada

To reach the resort or the backcountry trailheads, exit Highway 95 at either Lee Canyon or Kyle Canyon road. Both exits mark the northern boundary of the Las Vegas metropolitan area and are about a 30-minute drive from downtown.

The quality of skiing in the Spring Mountains varies dramatically year to year. Big winters can provide phenomenal backcountry riding, including a 4,000-plus-foot descent from the summit of Mount Charleston. In drought years, there might only be enough snow to ski mellow runs at Lee Canyon.

With an 860-foot vertical drop and four chairlifts accessing a couple dozen beginner and intermediate runs, Lee Canyon is a small resort with a friendly and playful vibe. Lift tickets are extremely affordable, ranging from $7–$70 based on demand, and $20–$40 most midweek days.

Tree runs and a terrain park are the highlights of the resort, while backcountry gates above the chairlifts entice advanced skiers who are prepared to earn their turns. The gates are only open for uphill travel when the snowpack is stable, as they unlock access to steep, avalanche-prone gullies and tree runs. Gate status is listed on the Lee Canyon website, as well as the resort’s daily conditions report.

There is no official avalanche forecast for the Spring Mountains, so if the gates are open, it’s a good sign that the peaks and ridges surrounding the resort are relatively safe to explore. Some of the best backcountry runs are found on North and South Sister, Mummy Mountain and the ridgeline west of Griffith Peak.

Those looking for a sledding hill, or even just gorgeous alpine views, should visit the town of Mount Charleston in Kyle Canyon. The town has few amenities and limited parking, however, so pack a lunch and arrive early after a fresh dump. The best snow play areas get extremely busy, leading law enforcement to turn cars around outside of town once the parking areas are full.

Hard-Earned Hot Springs

Leaving Mount Charleston, the highway begins a long, gradual descent toward Las Vegas, where temperatures are often 20 degrees warmer than in the mountains.

Temperatures in Las Vegas from December–February typically hover around 50 degrees—a bit chilly for hanging out poolside, but perfect for hiking in the desert. So don’t forget your trail shoes. The city is surrounded by spectacular hiking destinations, some of which are only accessible in the winter.

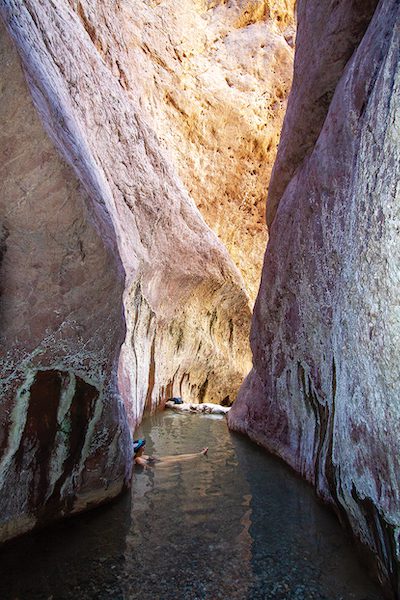

The Arizona Hot Springs offer an otherworldly soaking experience for those willing to earn it

The Red Rock Canyon National Conservation Area is one of the closest hiking areas and features a maze of trails that wind through stunning sandstone formations. Those who are game for a bit longer drive and a more strenuous trail can head to the Lake Mead National Recreation Area and spend the day hiking to hot springs on the Colorado River.

Boulder City, located 26 miles south of Las Vegas, is the jumping off point for Lake Mead, the Hoover Dam and the Colorado River. From Boulder City, a short drive leads to a pair of trails to the river, which are only open from October 1–May 15 due to dangerous hiking conditions in the extreme summer heat.

The Goldstrike Canyon Trail is a 5.3-mile out-and-back that drops 1,200 feet in elevation as it winds through craggy cliffs on its way to the water’s edge. Beyond beautiful views of a river stretch known as the Black Canyon, the reward for this strenuous hike is a chance to soak in riverside hot pools. The trail requires semi-technical scrambling, so it’s not recommended to bring dogs unless they are adept climbers or their owners are capable of carrying them through challenging sections.

The Arizona Hot Springs Trail is similar in length, just not quite as technical as the Goldstrike Canyon Trail. It starts at a dedicated trailhead across the Arizona state border from Boulder City. A 5-mile out-and-back hike with about 800 feet of elevation change leads through sandy washes to a series of hot pools trapped within the walls of a narrow slot canyon. The pools vary in temperature from 105–120 degrees and offer a relaxing place to soak, thanks to the work of locals who rebuild them year after year.

“We remove a few feet of gravel from the main pool every fall,” says one of the hot spring caretakers. “The floods also carry away some of the sandbags, so it can take us a couple days to make the springs soak-able again.”

Gravel washes into the pools during flash floods caused by summer thunderstorms. The flash flood season stretches from July–September, when the hiking trails are closed, but they can occur in any season. If thunderstorms are threatening, it’s advised to postpone hiking into the canyons until the skies clear.

A Colossal Amount of Concrete

Motoring back to Las Vegas from the hot springs allows for a quick stop at one of the most celebrated public works projects in U.S. history—the hulking Hoover Dam.

Built from 1931–1936, the massive wedge-shaped dam was constructed with enough concrete to pave a two-lane road from New York to San Francisco. While the 726-foot-tall dam is no longer the tallest in the United States (the Oroville Dam now holds that title, at 770 feet), the view from the Hoover Dam Bypass Bridge is no less impressive. A 15-minute walk from a free parking lot provides access to the pedestrian bridge and an unobstructed view straight down to the base of the dam nearly 900 feet below.

The vertigo-inducing view is arguably as entertaining as any free buzz you’ll find on the Strip, but if you’re too scared to peer over the edge of the bridge railing, don’t worry. What happens in Vegas stays in Vegas, and no one has to know.

Seth Lightcap is a writer and photographer from Olympic Valley who likes Coca-Cola, art that asks questions and mixing mountain adventures with urban culture.

No Comments