29 Nov Ribbons to the Rim

From ancient paths to modern highways, the routes leading to Lake Tahoe’s iconic shores are steeped in travel history

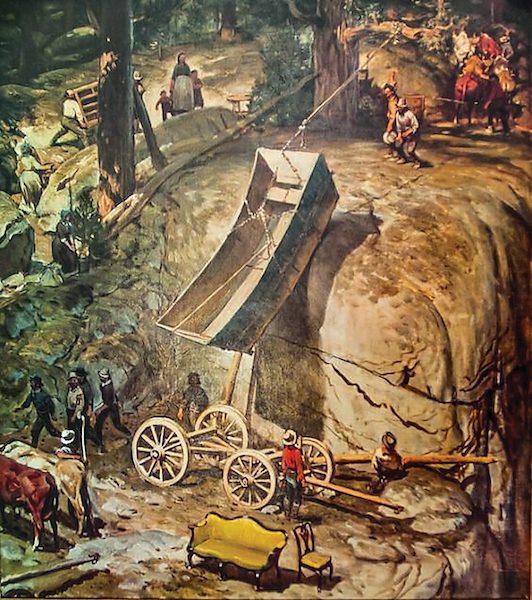

A scene depicting travel over Carson Pass, where pioneers often hauled disassembled wagons and their contents up and over steep escarpments

Long before pavement, survey crews or switchbacks, Tahoe’s first roads were simply trails—modest, efficient paths etched by the region’s indigenous peoples. These footways wound from the sagebrush valleys to the mountain lake and back again, with a few narrow tracks tracing the shoreline for gathering pinenuts, hunting game and collecting the brief summer’s bounty before the high-country winter sealed the landscape in snow.

Then came the newcomers. The mid-nineteenth-century migration west—first a trickle, then a deluge—pushed across the Sierra Nevada along the great overland trails. Families, prospectors and drifters followed the Carson Trail toward California, chasing gold and a new kind of dominion over

the land.

By 1849, wagon wheels rutted the earth where moccasins once tread. In a few short years, Anglo settlement reshaped Tahoe’s (and the West’s) destiny and erased much of what came before. But the rush west was only half the story.

When a gleam of silver was discovered in 1859 on the slopes of Nevada’s Mount Davidson, the tide reversed. The Comstock Lode at Virginia City triggered a stampede in the opposite direction, as fortune-seekers retraced their steps back over the Sierra. The same rugged corridors that had carried emigrants to California now funneled them eastward along what became variously known as the Great Bonanza Road, the Comstock Road, the Road to Washoe or simply the Silver Highway.

As the fever for gold and silver cooled, the Sierra’s rough wagon roads took on a gentler purpose.

By the early 1900s, Lake Tahoe had become a retreat for “rusticators” escaping the grit and noise of city life. Rail lines and lake steamers linked visitors to a growing constellation of lakeside lodges and camps. Getting there was still no easy feat—an automobile journey from San Francisco to “The Lake” could consume three or more long, jarring days—but the reward was clear water, pine air and mountain quiet.

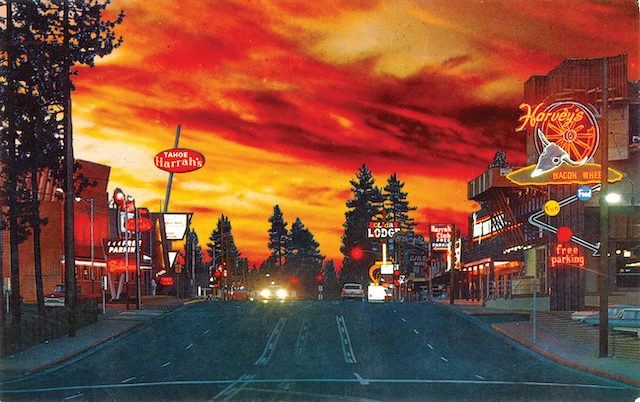

By the 1960s, Lake Tahoe had its own “Glitter Gulch” at the state line on U.S. Highway 50

Then came a new century, and with it, a new set of pressures: better cars, more tourists, the allure of Nevada’s casinos, the boom of ski culture and, eventually, the global spotlight of the 1960 Winter Olympics.

Each demand spurred another road, another improvement, another connection. Counties, states and federal agencies—sometimes in concert, often in conflict—joined forces with private enterprise to carve out the modern web of highways we know today.

Many of these modern roads still follow the same routes first walked by native peoples and later dragged over by emigrant wagons. In a few places, curious travelers can even trace a highway’s curve to an old railroad grade or forgotten toll road.

Tahoe’s byways are more than asphalt and guardrails. They are, in every sense, paths of persistence—routes carved by the twin forces of necessity and desire, guiding travelers ever upward from the valleys below to the blue heart of the Sierra Nevada.

The Lifeline Over Echo Summit

Of all the routes that reach Lake Tahoe’s shores, U.S. Highway 50 remains the most storied. Its lineage stretches back to the emigrant wagons that creaked over the Sierra in the 1840s along the Carson Trail. Over time, this corridor evolved from a rutted toll road into a main artery connecting California’s Central Valley and the Nevada desert.

A 1922 Morgan “Adventure Truck,” pictured overlooking Tahoe Valley from Echo Summit, was the perfect vehicle to explore Tahoe’s developing highways

For a century, the route twisted up from Carson City through Clear Creek Canyon—a steep, narrow grade that tested both wagons and early automobiles. That changed dramatically in the run-up to the 1960 Winter Olympics. Casino magnate Bill Harrah, ever the showman and strategist, saw the event as an opportunity. Harrah, whose glittering South Shore casino was far closer to the roulette wheel than the Olympic torch, launched a campaign to convince the press—and by extension, the world—that Harrah’s Lake Tahoe was the true gateway to the Games.

At his urging, Nevada fast-tracked the construction of a new four-lane highway over Spooner Summit, replacing the old Clear Creek grade. Harrah didn’t just cheer from the sidelines—he invested heavily, envisioning the day when sleek Cadillacs and tour buses would roll straight from the Nevada state capitol to his expanding lakeside empire. The project was a marvel of speed and coordination, and its completion just in time for the Olympics was a testament to what political pressure—and casino cash—can accomplish.

When the Games ended, the modern U.S. 50 remained, a wide ribbon of asphalt linking Carson City to the South Shore. The road’s improved alignment and grade changed the economics of the entire Tahoe Basin. What had been a seasonal destination suddenly became accessible year-round, a transformation that continues to shape Tahoe’s character today.

Gateway to the Biggest Little City

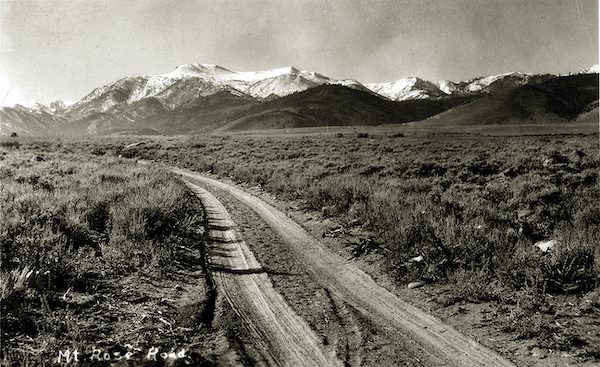

The Mount Rose Highway (Nevada State Route 431) provides arguably the most sought-after portal to the lake, climbing from Reno’s high desert through stands of mountain mahogany and aspen to the alpine saddle at Mount Rose Summit—the highest year-round pass in the Sierra Nevada. Its graceful, modern curves hide a story of urgency.

At the turn of the twentieth century, the Mount Rose Highway from Reno was a rutted wagon track connecting Galena‐area ranches to the eastern slope of the Carson Range, but washouts at the summit blocked travel to Lake Tahoe. By the 1920s, local businesses were advocating to reopen the route all the way to Incline Village

By the 1920s, motor clubs, business interests and Washoe County decried the lack of local access and pushed to reopen this previously abandoned wagon route from the region’s most populous city to Lake Tahoe.

Like U.S. 50, State Route 431 was rapidly upgraded ahead of the 1960 Winter Olympics, creating a vital connection between Reno’s rail lines and airfield and the Olympic venues near Tahoe City. The state poured resources into straightening and widening what had once been a narrow macadam road linking the Galena ranching area to Incline Village—a defunct lumber camp beginning to reinvent itself as a bustling year-round community.

Construction crews battled harsh winters to blast new cuts through granite and reinforce the steep grades with retaining walls, many of which remain in use. To improve snow removal—a primary consideration for any Tahoe-area roadway—engineers worked to shift the alignment from shadowy north-facing slopes to sunlit south-facing ones.

Today, in summer months, a large segment of the old route can still be walked, now quiet and forested, abandoned for nearly three-quarters of a century.

The highway opened just before the Games, its snowbanks towering over visiting motorists and Olympic dignitaries alike. The Mount Rose Highway remains both a scenic drive and an engineering feat—a road that climbs from desert sage to subalpine forest in less than 20 miles, tracing the evolution of Nevada’s high-country tourism in a single ascent.

The River Road to Tahoe City

From the former railroad-turned-lumber-town of Truckee, California State Route 89 meanders south along the Truckee River, tracing the same corridor that guided emigrants, loggers and early resort travelers to Tahoe’s West Shore.

The Bliss Family’s Lake Tahoe Railway & Transportation Company railroad line ran along the Truckee River between Truckee and Tahoe City. Much of the old railbed is occupied by today’s California State Route 89 and adjacent bike path

In the late 1800s, this was the main wagon route supplying Tahoe City, which was then little more than a cluster of hotels, a few sawmills and a commercial pier. The coming of the railroad to Truckee in 1868—and Lake Tahoe Railway & Transportation Company’s subsequent rail line to Tahoe in 1900—transformed the road into a vital link between rail passengers connecting to the Bliss family’s Tahoe Tavern resort and the lake’s fleet of steamers.

Automobiles soon followed. By the 1910s, “River Road,” as locals called it, became a favorite touring route for San Franciscans arriving by train. Its gentle grade and riverside scenery made it one of the most beautiful approaches to the lake, and it remains so today. Though modernized and widened, much of State Route 89 still hugs the same bends of the river that early travelers splashed across in wagons, the air filled then—as now—with the sound of rushing water and pine-scented wind.

Shortcut to the North Shore

If California State Route 89 was the elegant old mainline, State Route 267 was its pragmatic younger sibling—a shortcut linking Truckee to Tahoe’s North Shore over Brockway Summit.

The corridor began as a rough logging road in the 1860s, serving the mills that harvested the thick stands of timber above Martis Valley. By the turn of the twentieth century, as resorts sprang up around Kings Beach and Crystal Bay, the road was improved for wagons and early automobiles carrying vacationers and gamblers to the lake.

Today’s State Route 267 retains that same spirit of directness. From Truckee, it climbs briskly through open forest and crests at 7,200 feet before descending in sweeping curves to the blue expanse of Tahoe.

Though now a well-engineered modern highway, it still delivers what it always promised: the fastest, most dramatic gateway from the transcontinental rails to the cool waters and bright lights of the North Shore.

Old Pony Express Road

Long before there was a highway sign on Kingsbury Grade (Nevada State Route 207), it was Daggett Pass Road, a rough mountain corridor linking the Carson Valley to Tahoe’s South Shore.

Hairpin turns were a hallmark of Daggett Pass Road (Kingsbury Grade)

In 1860, Pony Express riders thundered up this very route, carrying mail between Sacramento and St. Joseph, Missouri, in record time. The same steep climb that challenges modern cars once tested horses and riders racing against time and weather.

By the 1870s, the road became a toll route, vital for hauling lumber from Tahoe Basin sawmills to the mines of Virginia City. Later, as mining waned and recreation took hold, the road was widened, graded and renamed Kingsbury Grade, honoring early rancher David Kingsbury.

The alignment still follows the historic corridor—one of the few stretches where you can drive, in modern comfort, along the same path once pounded by Pony Express hooves.

Present-day State Route 207 descends dramatically into the Carson Valley, offering panoramic views that seem little changed since the express riders first crested the summit.

From Timber to Tourists

Nevada State Route 28 between Incline Village and Sand Harbor is a lakeside pleasure drive—a scenic ribbon of asphalt where cyclists, beachgoers and photographers share the road and an adjacent new multi-use trail. But in the nineteenth century, this tranquil stretch was anything but leisurely.

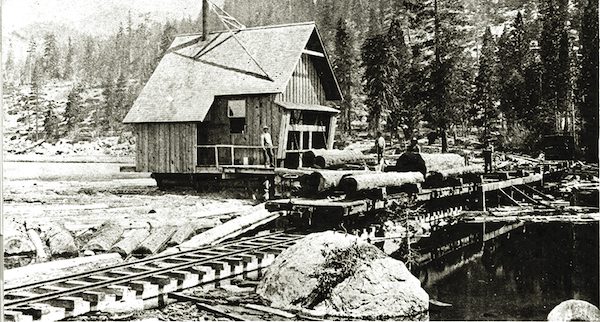

The Sierra Nevada Wood & Lumber Company Railway at Crystal Bay in the 1890s

Here ran the Sierra Nevada Wood and Lumber Company’s railroad, a remarkable industrial system that connected Tahoe’s timber to the hungry mines of the Comstock Lode. Logs floated across the lake to the pier at Sand Harbor, where steam locomotives hauled them northward to a sawmill located at what later became the Ponderosa Ranch parking lot.

From there, freshly cut lumber was winched up the west slope of the Carson Range on an ingenious railway—the “Great Incline”—then shot down wooden flumes on the east slope to the Virginia & Truckee Railroad below. The lumber supplied the booming cities of Virginia City and Gold Hill, fueling the Comstock’s silver fortune.

When the lumber era faded, the railbed remained dormant until it was reborn as a scenic automobile route. The ghosts of the old logging line still linger in the topography, as gentle grades and broad curves that once served locomotives now cradle cars and bicycles.

Old and new roads run parallel over the Sierra Nevada along California State Route 88

Emigrant Trail Reborn

Farther south, California State Route 88 (the Carson Pass Highway) preserves one of the oldest pioneer corridors across the Sierra. This route follows the Mormon Emigrant Trail, the same line used by nineteenth-century settlers and gold-seekers hauling wagons toward the California foothills.

Although outside the immediate Tahoe Basin, the route played an essential role in opening the region to commerce and tourism. It served emigrants, teamsters, stagecoaches and, later, automobile adventurers.

Today’s smooth pavement hides a path of enormous hardship—snow, floods and steep talus slopes once claimed wagons and livestock by the score. Travelers who pull over near Caples Lake or Hope Valley can still glimpse remnants of the old wagon grades etched into the forest.

A Web of Roads, A Web of Stories

Other regional roads have their own stories—most notably U.S. Highway 40 (known locally as Old Highway 40, which was part of the coast-to-coast Lincoln Highway) and Interstate 80.

Each of these routes, whether carved through granite or laid atop forgotten tracks, tells a chapter in Tahoe’s ongoing saga. The ancient trails of the Washoe and Paiute gave way to the wagon roads of the forty-niners; the toll roads of the Comstock era became the modern highways we know today.

And when the Olympic flame burned in the Sierra in 1960, it didn’t just light the slopes—it illuminated a new era of ambition, innovation and reinvention that still shapes how we arrive at this storied lake.

Bill Watson is the curator of Thunderbird Lake Tahoe.

A Highway Magazine from February 1925, when articles about Tahoe’s newly built roads appeared in highway publications around the world

Walk the Old Mount Rose Highway

Explore a section of the former Nevada State Route 431 by parking at the small turnout at the base of the steep grade, about half a mile north of Incline Village’s Apollo Drive, on the north side of the modern Mount Rose Highway. In fall, the colors are stunning as you traverse the roughly 2-mile route to Incline Lake along the old roadbed.

Explore a Forgotten Stretch of U.S. 50

Just south of Meyers lies a little-used remnant of the old “Meyers Grade”—an original alignment of U.S. Highway 50 that climbed up toward Echo Summit and was phased out as the highway was realigned in the 1930s and ’40s. Park at the turnout on South Upper Truckee Road (just off U.S. 50 in Meyers) and follow the grade upward for about 1.5 miles. You’ll walk on the old pavement in a quiet forest setting where road history meets solitude.

Enjoy the Scenery on the East Shore Trail

The scenic, family-friendly East Shore Trail parallels Nevada State Route 28 for 3 miles from Incline Village to Sand Harbor. The modern highway overlays a historic rail line that ran from a Sand Harbor pier to a sawmill near today’s Tunnel Creek Café. Whether on foot or by bike, it’s a stunning way to take in the East Shore—with panoramic views, hidden beach accesses and interpretive signs along the way.

No Comments