26 Apr American Pika Clinging to Existence in Tahoe

The furry, high-elevation animal has gone extinct in sections of Tahoe—land that was once its core habitat

A scampering ball of fur with Mickey Mouse–round ears and a miniature bouquet of flowers in its mouth—the American pika has long been a prized sighting for those who venture into the high mountains of the West.

And just as its high-pitched call has been a sure sign to backcountry travelers that they’ve reached the alpine, the pika’s struggles in warming temperatures has signaled bigger changes at hand to the scientific community.

When a study published in the summer of 2017 reported pikas locally extinct in the Truckee–North Lake Tahoe area, it made headlines and raised the alarm once again to protect the region’s prized wild places.

The pika, a small, high-altitude relative of the rabbit, has long been considered a “canary in the coal mine” for the effects of climate change on the Sierra Nevada, as its sensitivity to warming temperatures drive it higher and higher in search of suitable habitat.

A 1.9 degree Celsius increase in temperatures in the region since 1910 has left the local population split, remaining only along the Sierra Crest around the Granite Chief Wilderness to the west and in the Mt. Rose Wilderness to the east, seeking cooler summer temperatures and sufficient snowpack to insulate their winter dens.

Scientists have tracked pikas disappearing elsewhere in the Sierra and in the Great Basin, generally along the edges of their traditional territory, but this represents a loss in what is considered their core habitat.

So what does it mean for this particular coal mine if the canary is dead? What implications does this local extinction have for pikas as a species, for other species in the Tahoe area and the region’s climate?

“These changes can leave tremendous holes punched through our ecosystems,” says Shaye Wolf, climate science director for the Center for Biological Diversity. “Losing these species is heart-wrenching, but it also jeopardizes people because we rely on healthy ecosystems for things like our water supply.”

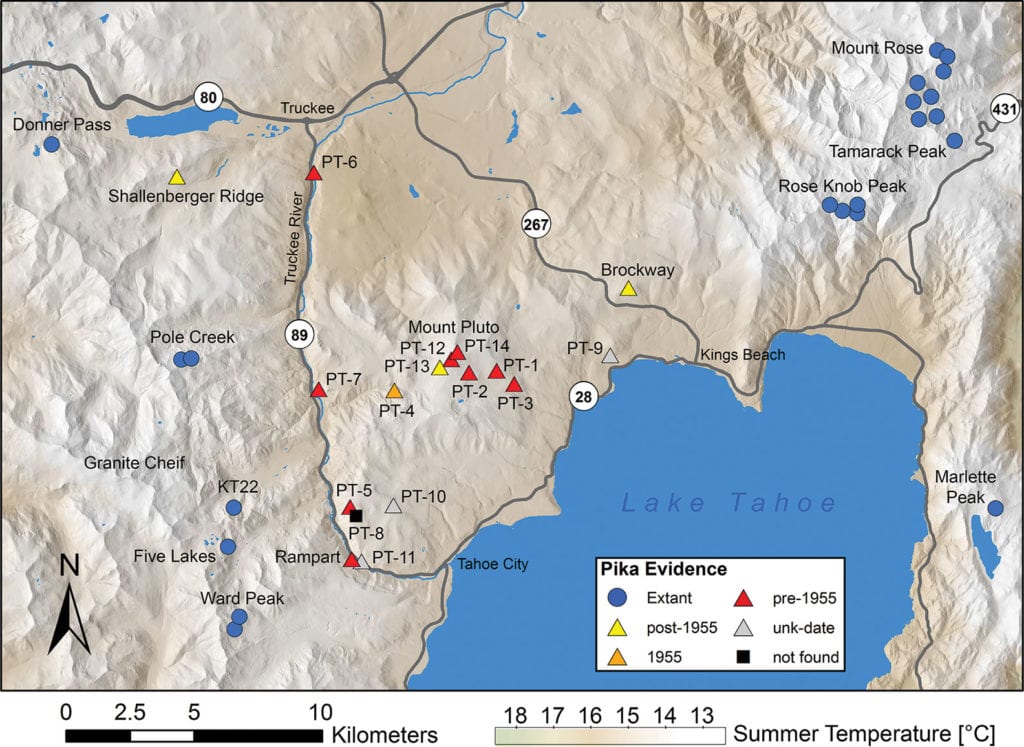

Sites surveyed for American pikas in the North Lake Tahoe area. The Pluto triangle is bounded by Lake Tahoe, Highway 267 and the Truckee River adjacent to Highway 89. Current signs of pikas were found both east and west of the Pluto triangle; nearly all sites within the triangle yielded old fecal pellets.

Sites surveyed for American pikas in the North Lake Tahoe area. The Pluto triangle is bounded by Lake Tahoe, Highway 267 and the Truckee River adjacent to Highway 89. Current signs of pikas were found both east and west of the Pluto triangle; nearly all sites within the triangle yielded old fecal pellets.

Local Extinction

Scrambling over the loose talus fields of the Truckee–Tahoe region since 2011, biologist Joseph Stewart from University of California, Santa Cruz, discovered the small mammal has disappeared from a 65-square-mile area between Tahoe City, Kings Beach and Truckee.

He reported these findings in Apparent Climate-Mediated Loss and Fragmentation of Core Habitat of the American Pika, published with David Wright and Katherine Heckman in August 2017.

“I found jaw-droppingly large areas of habitat where they seem to have existed as recently as between the ’60s and ’90s,” Stewart says. “But finally after six years of exhaustive surveying, we concluded there were no more pikas here.”

Projecting forward, estimates show a 97 percent loss of habitat in the Sierra Nevada for pikas by 2050, he says.

Pikas primarily call alpine talus (broken rock) fields in western U.S. mountain ranges home. From these high-elevation locales, they can access meadows to forage and rely on snow cover each winter to insulate their dens.

“We’re looking at huge biological changes. The size of the areas that pikas are disappearing from are on the scale of the last ice age, but they’re happening now over a matter of decades, not on geological time,” Stewart says.

Local extinction may not sound particularly bad, with populations remaining to both the east and west of the surveyed area, but increased isolation comes with its own risks beyond those of warming temperatures.

“The gap is large enough that we don’t think there’s any genetic connectivity between populations,” Stewart says. “So if one population blinks out, there is no rescue effect from other nearby populations.”

Wolf says that pikas have been on conservationists’ radar for quite some time.

“Joseph Stewart has done incredible work in California,” Wolf says. “His study is just the latest research that reinforces that pikas are in serious danger from climate change.”

Wolf authored two petitions—one at the federal level and the other at the state level—to get pikas protected under the Endangered Species Act in 2007. That effort failed in 2009.

“Trying to get a species listed because it’s threatened by climate change has been difficult when there is a lot of political pressure not to acknowledge the threat of climate change,” Wolf says. “These local extinctions only increase the risk of global extinction.”

Alpine chipmunks are among the species struggling for survival in the Sierra, courtesy photo

Alpine chipmunks are among the species struggling for survival in the Sierra, courtesy photo

Other Threatened Species

Pikas, a prey source for raptors, coyotes and weasels, aren’t the only species threatened or already gone from the forests, meadows and mountains of the Tahoe–Truckee region.

The white-tailed hare is also locally extinct in the Desolation Wilderness region, Stewart says, and alpine chipmunks have disappeared from 90 percent of their historic range.

Predators like the Sierra Nevada red fox and Pacific fisher are struggling, and other carnivores that were wiped out of the region a century ago—like wolves, grizzly bears and wolverines—face stacked odds against their return, says Noah Greenwald, endangered species director for the Center for Biological Diversity.

Pacific fisher, courtesy photo

Fishers, a relative of the wolverine with the unique talent for hunting porcupine, were also recently denied endangered status. They once spanned the entire Sierra, but are now absent from the Tahoe region and continue to be threatened by loss of habitat and pesticides used in illegal marijuana grows, Greenwald says.

“There’s also the massive tree mortality in the Southern Sierra,” Greenwald adds. “That affects habitat for these animals.”

And as animals retreat uphill at a rate that outpaces plants’ slower migration to higher elevation, ecosystems will become mismatched, says Wolf. Pollinators will be separated from the trees and flowers that depend on them.

“We’ve already pushed things too far—climate change has already caused very serious harm to ourselves and to other species,” Wolf says. “And there are worse consequences to come if we don’t take really significant action.”

American pika, photo courtesy Will Thompson, U.S. Geological Survey

American pika, photo courtesy Will Thompson, U.S. Geological Survey

Taking Action

While scientists point toward the urgent need for global greenhouse gas emissions action—without which current projections show one in six species going extinct across the planet—there are local actions that can be taken as well.

“What happens next depends on our actions today,” Stewart says. “You could potentially breed animals to be more resistant to climate change, or you could attempt habitat modifications.”

Wolf says ensuring habitat connectivity and reducing stressors—such as limiting cattle or sheep grazing around pika habitat, for example—could also help.

With the Town of Truckee and City of South Lake Tahoe setting goals for 100 percent renewable energy, along with ski resort Squaw Valley Alpine Meadows pledging to use 100 percent clean energy, Wolf sees hope in local action.

“Local communities embracing and trying to adopt 100 percent clean energy is incredibly important,” Wolf says. “Since we have an administration rolling back progress, there is a tremendous need to act at local and state levels. It will create so many benefits for communities, for job creation, health and, of course, climate.”

What happens to the remaining pikas on the slopes of Mt. Rose, the talus fields of Granite Chief and so many other species across the West remains a troubling question. Conservationists hope that the worst effects of a warming planet and habitat loss can be held at bay, giving these unique and important animals a fighting chance at survival.

Greyson Howard is a Truckee-based writer. Find more of his work at greysonhowardmedia.com.

No Comments