01 May Kit Carson: The True Pathfinder of the Frontier

Lauded as a hero for his courageous contributions to his country, the rugged outdoorsman also had a darker side

Perhaps more than anyone, Kit Carson witnessed the dawn of the American West.

The unassuming man of small stature was not only at hand for the most seminal moments in the early days of the West, he played a pivotal role in its assimilation into the United States.

The West hinged on his deeds, and swung the way of America because of his competence.

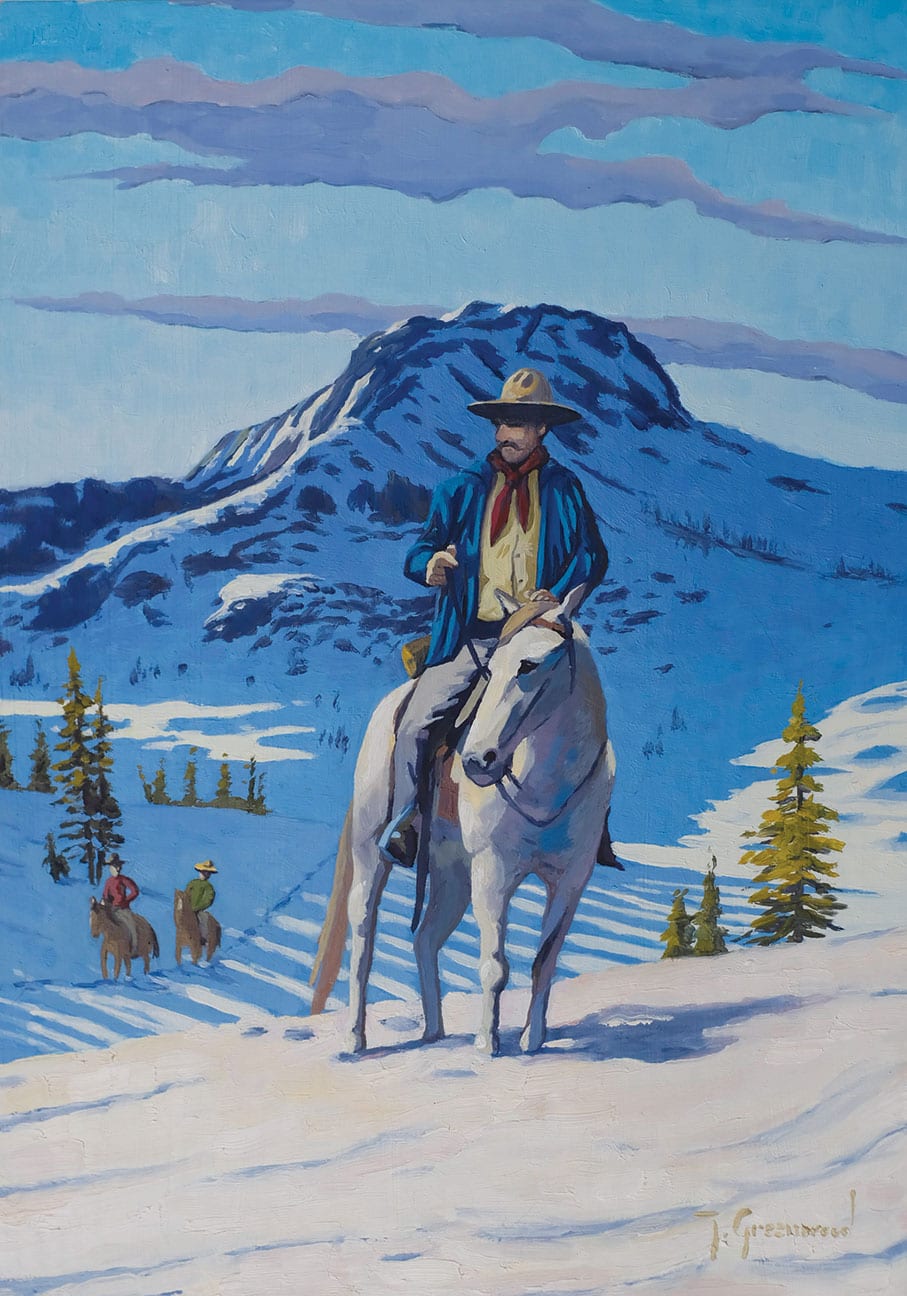

While Carson never visited Lake Tahoe, he led the exploration of the valleys, peaks and mountain passages immediately adjacent, as reflected by the fact that Carson City, the Carson Valley, Carson River and Carson Pass all bear his name.

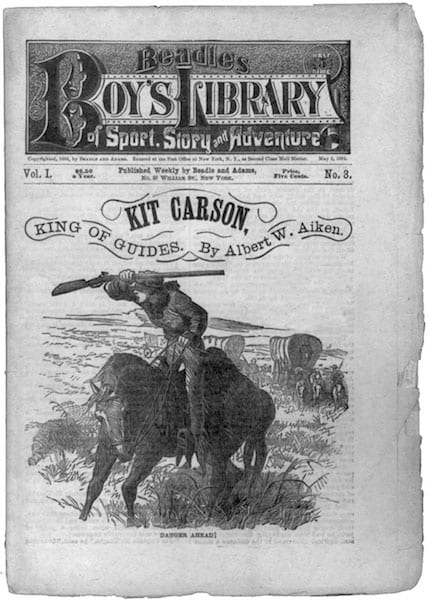

Kit Carson, King of Guides, by Albert W. Aiken, 1884, courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

Carson spent his youth haunting the rugged watersheds of the untamed nineteenth-century West as a fur trapper. He led expeditions over remote mountain passes into fugitive lands teeming with grizzly bears, venomous snakes, hostile natives and murderous bandits.

Carson played an unofficial but crucial role in the Mexican-American War and the American conquest of California.

He befriended Native American tribes, marrying into them while assimilating their skillful and integrative approach to the feral land. But he fought the natives, too, at times ruthlessly, burning villages of the Navajo before marching them to a paltry reservation.

Carson personified the ambivalence we have toward the early West—on the one hand embodying freedom, courage, resourcefulness and self-reliance but also the racial animosity, brutality and wanton violence.

He wasn’t the gunslinger of Hollywood dreams, but he was a crack marksman with a rifle or a pistol.

He wasn’t an outlaw, because he roamed the West before there were any laws to be followed.

The West knew no shortage of whiskey-swilling, prostitute-chasing pioneers, but Carson rarely drank or chased women. “Clean as a hound’s tooth” was how he was described by associates.

Carson stood about 5 feet 4 inches with a surprising reserve of sinewy strength, a decisive man of action whose favorite phrase was “done so.” He was fiercely loyal and reliable in a pinch, though too taciturn to boast of accomplishments.

Carson’s personality had an underside, however. He had a quick temper, which could turn violent abruptly, and he wasn’t above brutality. Carson was of Scotch Irish descent and he harbored his people’s legendary propensity to nurse a grudge.

But there was no more consummate outdoorsman of his day.

Carson could break a wild horse or cure a hobbled mule. He knew how to orient a camp against raids and could be on his horse and at the ready with a gun in no time. He was a prodigious hunter, an adept fisherman and could smith a gun part or forge pieces of equipment as required.

His skill as a tracker was peerless. He knew watersheds with the feel of a modern hydrologist and he maintained a mapmaker’s eye for landscape, serving him well in days as a scout.

For Carson, topography revealed its secret watering holes in the swerve of its swales and the bend of its hills. Carson knew the way to cross a desert and stave off thirst by extracting water from cactus roots.

During his time as a young fur trapper, he acquired fluency in French and Spanish. He grew to know enough native languages—including Navajo, Arapaho, Cheyenne, Blackfeet and Ute—to become a crafty negotiator with various tribes, brokering both trades and ceasefires.

But he was also illiterate, a fact that caused him no little grief. The inferiority complex he harbored as a result made him comfortable playing deferential roles to men like John C. Fremont, the politician, soldier and explorer.

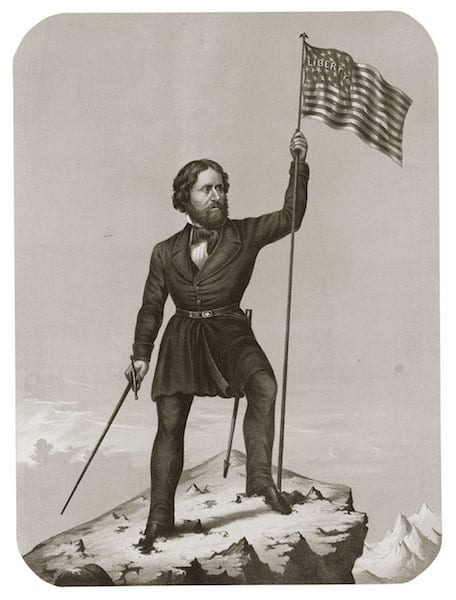

Illustration of John C. Fremont, courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

Fremont, of course, along with cartographer Charles Preuss, was the first recorded white man to lay eyes on Lake Tahoe.

He espied it from the summit of Red Lake Peak, situated just north of what is today called Carson Pass, so-called because it was Kit Carson who traced the tough and precipitous trail through the Sierra in the winter of 1844.

While Fremont’s frequent expeditions into the American West earned him the nickname “The Pathfinder,” it was his less educated and well connected scout, Carson, who invariably found the paths.

Kit in the Sierra

Kit Carson’s relation to Lake Tahoe appears obvious. After all, Carson City, the Carson Valley and the Carson River—all in proximity to the Tahoe Basin—are christened in his honor.

Carson Pass traces the modern day Highway 88 out of Minden, Nevada, into Alpine County, California, through Paynesville past Caple Lakes and Kirkwood Mountain Resort, before swerving by Silver Lake and down the more gentle grade of the Sierra’s western slope toward Stockton.

The pass is named after Kit Carson because he forged the trail taken by 24 men and 67 pack animals in the dead of winter in 1844.

It was during this winter, on Valentine’s Day, that Fremont and Preuss hoofed it to the top of Red Lake Peak to get the lay of the land and saw the azure waters of Tahoe.

“With Mr. Preuss, I ascended today the highest peak to the right, from which we had a beautiful view of a mountain lake at our feet, about fifteen miles in length and so entirely surrounded by mountains that we could not discover an outlet,” Fremont wrote in his expedition report for February 14, 1844—perhaps an underwhelming description of the largest alpine lake in North America.

But the terse mention indicates Fremont’s weariness and concern after a month of trudging along the snow-laden ridgelines, using mauls to hew a rough path through the head-high snowpack.

In his diary, Preuss never mentions Tahoe. While it’s unlikely that Carson ever glimpsed Tahoe, he was the biggest reason Fremont did.

Carson was forced to muster all his skill as a trail scout to ensure Fremont’s explorers did not suffer the same fate the Donner Party would three years later.

Carson found himself in the Sierra after Fremont had enlisted him to map the Oregon Trail.

After a successful journey—mapping the Snake and Columbia rivers and landmarks like Mount St. Helens and Mount Hood—Fremont gathered additional provisions in Vancouver and turned back east.

But instead of heading back to Washington D.C. as planned, Fremont and Carson opted to turn south along the eastern flank of the Cascade Range.

The principle reason for the detour was to locate the mythical Buenaventura River, a majestic waterway fabricated out of cobbled Western legends that supposedly flowed westward from the Rocky Mountains across the western shelf of the continent to the Pacific Ocean. The man who found the Buenaventura could obtain nationwide glory.

The fact that the rivers flowing west from the Continental Divide were swallowed by the vast geographical sink that Fremont himself would name the Great Basin was not yet a geographical reality in the early part of the nineteenth century.

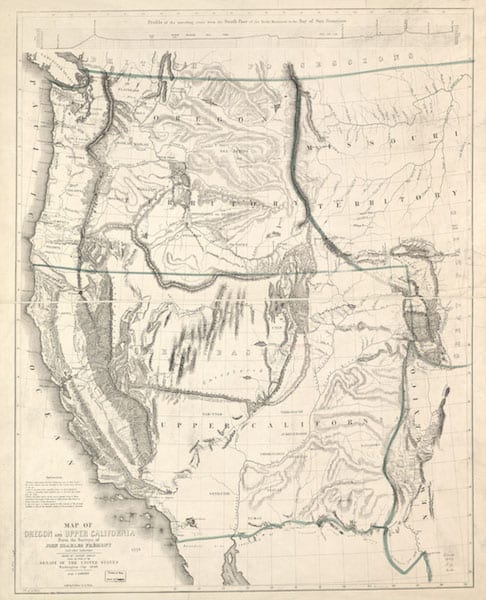

Map of Oregon and upper California from the surveys of John C. Fremont and other authorities, 1848, courtesy Library of Congress Geography and Map Division

This realization eventually set in as Carson led the party to Pyramid Lake at the terminus of the Truckee River on January 13, 1844, and continued along the precipitous escarpment of the Eastern Sierra.

“With every stream I now expected to see the great Buenaventura and Carson hurried eagerly to search on every one we reached for beaver cuttings, which he always maintained we should find only on waters that ran to the Pacific and the absence of such signs was to him a sure indication that the water had no outlet from the great basin,” Fremont wrote of the journey through the Washoe Valley in early January 1844.

By this time, a brutal fog hung in the Washoe Valley for days at a time. Game was scarce, and so Fremont decided they would brave the Sierra to the west rather than the spare desert to the east.

Fremont was partly persuaded by Carson’s descriptions of the Sacramento Valley as a place abounding in game and forage capable of sustaining the ragged band. Carson had been to California 15 years prior, hunting beavers.

“I therefore determined to abandon my eastern course and to cross the Sierra Nevada into the valley of the Sacramento, wherever a practicable pass could be found,” Fremont wrote on January 18.

The Washoe Indians encountered by Fremont and Carson recommended the group follow the Truckee River up to Donner Lake, where they only had to gain the pass before following one of two rivers—the Yuba or American—west into the fertile valley.

But for unknown reasons, Fremont bent southward. His group located and trudged along the Carson River—with Fremont naming it after his trusty scout—and ventured as far south as the Bridgeport Valley. The men then followed the Walker River into the mountains, but found the depth of the snowpack too formidable and the terrain too rugged.

The party descended back into the Carson Valley and moved north before making another foray into the hills, this time following the east fork of the Carson River along what is now Carson Pass, roughly following Highway 88.

The natives repeatedly warned Fremont and Carson about high snow drifts and the impassibility of the steep spine of the Sierra in winter, but the men persisted.

In late January, the group set off from what is today is the Minden-Gardnerville area, using a 10-person alternating system to break the snow sufficiently to create a path for the pack animals carrying scientific equipment and biological specimens collected by Fremont throughout the journey.

On February 5, after the mercury dipped below 10 degrees overnight, the Native American guide whom Fremont had taken to calling Melo deserted the party, leaving Carson as the primary route finder.

The party stuck to the wind-scoured ridges rather than the snow-steeped river valleys.

“The snow is so horribly deep, and we can cover only a few miles each day,” Preuss wrote in his diary on February 6. “I am walking almost barefoot. This surpasses all the hardships that I have experienced until now.”

Nevertheless, on February 6, Carson provided optimism, spotting Mount Diablo from the trail.

“There is the little mountain—it is 15 years ago since I saw it, but I am just as sure as if I had seen it yesterday,” said Carson, as quoted in Fremont’s journal.

By February 11, provisions had run low and morale sank lower when the group had to kill a beloved dog to stave off hunger.

The group resorted to eating horses and mules for sustenance.

“We had tonight an extraordinary dinner—pea soup, mule and dog,” Fremont wrote on February 13.

The next morning Fremont and Preuss espied Lake Tahoe.

They trudged on through sporadic snowstorms for a week before gaining the pass on February 21.

“We now considered ourselves victorious over the mountain,” Fremont wrote. “But this was not a case in which the descent was facile.”

In fact, the slippery snow- and ice-covered rocks and rushing streams proved precarious for the provision-starved band of beleaguered travelers, but Carson once again proved indispensable, as he remembered the area from hunting beavers 15 years prior.

Finally, on March 6, Fremont and Carson stumbled onto the ranch of John Sutter in the Sacramento Valley, where they were lavished with food, drinks and the comforts of civilization.

Members of the party were “in as poor condition as men could possibly be,” Carson later said. One man was “deranged and perfectly wild from the effects of starvation.”

Carson recalled the mules being so hungry they ate leather off the saddles, as well as one another’s tails.

But by carving Carson Pass through the Sierra in the dead of winter, Carson built another layer to his legend and his growing status as a hero of the American West.

Youth and the Wanderlust

The 11th of 14 sons, Christopher “Kit” Carson was born in Kentucky on Christmas Eve in 1809—the same state and year as Abraham Lincoln. When Carson was a year old, his family headed west to Missouri.

Carson earned his nickname almost immediately, being smaller than his brothers and sisters. But his family soon learned to respect the boy’s burgeoning moxy and the courage he casually displayed running around the family farm in Boone’s Lick, Missouri.

In 1818, Carson’s father was killed by a falling limb, forcing the young man to abandon his schooling at age 14 to help earn money. His lack of schooling would weigh heavily on his self worth for the rest of his life.

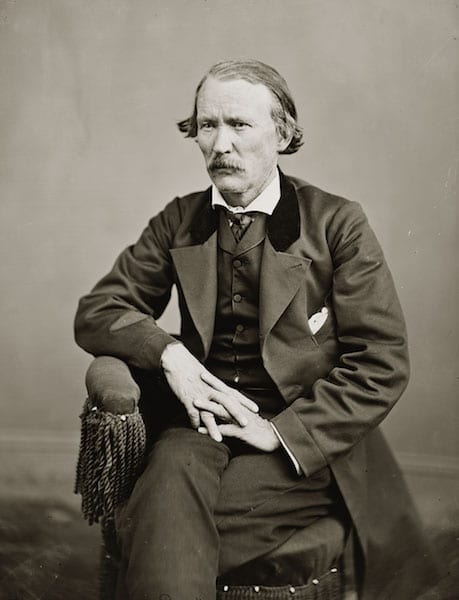

Kit Carson, pictured between 1860 and 1875, courtesy Brady-Handy photograph collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

“I jumped to my rifle and threw down my spelling book, and thar it lies,” Carson said at the end of his life while dictating his memoirs.

Soon after his father’s demise, Carson was apprenticed to a saddle repairman named David Workman in Franklin, Missouri, situated at the eastern terminus of the Santa Fe Trail.

In Franklin, Carson was exposed to the adventurous tales of fur traders headed west into the territory of New Mexico. Soon Carson abandoned the saddle repair enterprise, which he considered laborious, and set out on the trail in August 1826.

For the next two decades Carson roamed the hinterlands of the continent, venturing as far as the Pacific Northwest. Learning from legendary trappers like Jim Bridger, Carson spent years hunting beaver across the rugged West, acquiring comprehensive knowledge of the varied landscape of Colorado, Nevada, Utah and Wyoming.

He befriended many Native Americans, and made enemies too. He learned the natives’ sign language, their usage of smoke signals and acquired their skillful integration with the Western landscape.

The surest sign of Carson’s rapprochement with the indigenous culture of the American West came in 1835 at an annual gathering of fur trappers and native tribes held on the banks of the Green River in Wyoming—where the wild men and women of the West gathered to drink, gamble and carouse.

There, Carson courted a great Arapaho beauty who went by the name of Singing Grass.

But he had to fight to win her hand.

He was in direct competition for her charms with Joseph Chouinard—a large French-Canadian man referred to as “The Bully of the Mountains.”

Carson harbored a lifetime hatred of bullies and relished any opportunity to set them right. In the case of Chouinard, the two men got into a heated argument over Singing Grass before discharging their guns at close range. While Chouinard’s bullet grazed Carson just under his ear, earning him a scar he would wear the rest of his days, Carson’s bullet struck Chouinard in the hand, tearing off his thumb.

Historians are divided about whether Chouinard died in the encounter, but his defeat left Carson free to pursue and eventually marry Singing Grass, who went on to bear Carson two daughters. Singing Grass died of fever shortly after giving birth to the second child.

While Carson’s marriage to Singing Grass exhibited his respect of Native Americans and their way of life, the mountain man also spent much of his youth in open hostility with natives of the West.

Carson hated the Blackfeet tribe in particular after catching an arrow in the shoulder during a battle in the early 1830s. From then on, he bore a grudge against the tribe and never passed an opportunity to confront its members.

But by 1840, the Blackfeet were the least of his concerns, as Carson was left contemplating his future as the fur trapping industry declined due to shifting fashions and a depleted beaver population.

During a trip back to Boone’s Lick to see family and plot his next move, fate intervened in the form of John C. Fremont.

Pathfinding

Carson wasn’t as famous as he would later become, but when Fremont met the small, reserved man on a riverboat outside of St. Louis in 1842, his prowess as an outdoorsman was well established in certain circles.

Fremont was immediately impressed with Carson’s “modesty and gentleness” and offered him work as a scout for a grand expedition into the American West.

“I’ve been some time in the mountains,” Carson replied. “I could guide you to any point you wish to go.”

At the time, Fremont’s mission was to map the watersheds and other landmarks along the Oregon Trail to smooth the journey for the swelling number of pioneers.

So on June 12, 1942, Fremont gathered his sundry collection of 25 adventurers, loaded wagons with cartography supplies, scientific equipment and inflatable rubber boats, and set off west of Kansas City.

It wasn’t long after the group ventured into the ocean of prairie that Carson proved his mettle.

Fearing a war party of Native Americans intent on a raid, the camp sounded an alarm one morning and Carson climbed up on his horse in a flash and set off across the prairie to reconnoiter.

“Mounted on a fine horse, without a saddle, and scouring bareheaded over the prairies, Kit was one of the finest pictures of a horseman I have ever seen,” Fremont wrote.

The alarm proved false, as it was only a herd of curious elk, but the episode proved characteristic of the decisive and brave Carson.

It was the first of many occasions when Fremont used Carson’s multifaceted talent to further his own exploratory ambitions.

Trained to Western Enterprise

After Fremont and Carson recuperated sufficiently from their arduous Sierra Nevada crossing, the pair led the group to further explore California’s expansive and diverse geography.

During this phase of the journey, one incident in particular contributed to the increasing profile of Carson in the national imagination.

As Fremont’s men navigated the Mojave desert, they came upon two straggling travelers, an older Mexican man and a boy, in poor condition. The pair divulged they had been traveling with a large party that included two more men and two women when they were ambushed by natives, who killed the two men and staked the women to the ground, sexually mutilated and killed them, and stole the party’s 30 horses.

After hearing the tale, Carson set off immediately with his friend Alexis Godey in the direction the culprits had fled. It took days of hard riding through pitiless desert, but the two men finally located the raiders. Despite their meager numbers, Carson and Godey rushed the camp, killing two of the thieves while scattering the rest. They scalped the dead and made off with all 30 of the stolen horses. The mounts were restored to the Mexican man and the boy in short order.

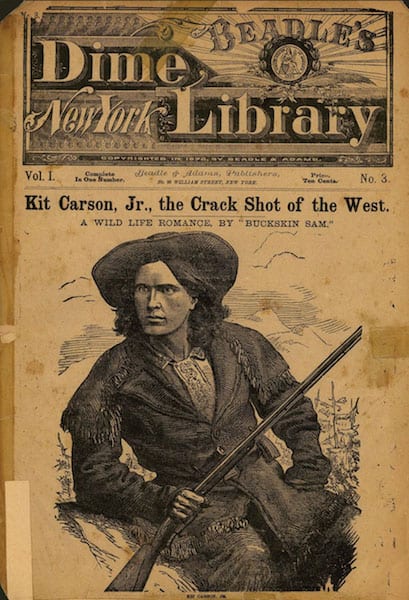

Kit Carson dime novel, courtesy photo

The feat stunned Fremont, who thought Carson would surely perish in the endeavor.

“Two men, in a savage desert, pursue day and night an unknown body of Indians into the defiles of an unknown mountain—attack them on sight, without counting numbers—and defeat them in an instant,” he wrote in his report.

Fremont said that episode more than any other demonstrated that Carson “trained to western enterprise from early life.”

After Fremont published his report, the episode became a central anecdote in the dime novels printed about Carson, who was lauded throughout the nation as a true Western hero.

The Klamath Lake Massacre

After the Carson Pass and Mojave Desert episodes, Fremont returned to Washington D.C. bedraggled, a little worse for the wear and more than a year late. Carson rode back to Taos, New Mexico, where he married Josefa Jaramillo, the daughter of a prominent Mexican family.

While Carson laid low, Fremont reveled in the glory created by the publication of his account of his Western adventures, which were written with the help of his literary wife, Jessie Benton.

Fremont’s report had two major effects: It increased the number of pioneers who struck out for the Oregon Trail, and it made Kit Carson a household name.

By the following year, 1846, Carson and Fremont were back exploring the West.

One night while camping on the shores of Klamath Lake in southern Oregon, Carson awoke to notice Fremont had neglected to post sentinels before packing it in for the night. A little put off but not thinking too much of it, Carson drifted back to sleep.

He was soon awakened by a dull thud. When he looked toward Basil Lajeunesse—a French trapper who had been traveling with Carson since their trapping days—he saw a disturbing sight. The man’s head was cleaved in two with a hatchet. Carson jumped into action with characteristic swiftness, rousing the other sleepers. The camp was encircled by hostile natives, who fired a barrage of arrows into the camp, killing two members of the party.

Carson and the others rejoined the arrows with gunfire and Carson, in particular, fended off his would-be killers with his customary calmness and skill.

In the midst of the fray, one fighter broke through and engaged the fight at close range. He was riddled with bullets and soon perished. Carson would later say he was the bravest Native American he ever beheld. But after the battle was over and three members of the party lay slaughtered, Carson vented his spleen by repeatedly hacking the face of the dead attacker.

Carson was not alone in thirsting for vengeance.

The next day, Fremont ordered the party to circumnavigate the lake. They soon happened upon a Klamath settlement called Dokdokwas and turned their guns, swords and other weapons on the inhabitants.

“They were severely punished,” Carson described of the incident in his memoirs.

All told, more than a dozen Native Americans were slaughtered and the houses of the village were set on fire—a scene Carson would later call “a beautiful sight.”

Contemporary historians cast doubt on the aptness of the revenge. Judging by Fremont’s descriptions, historians now believe members of the Modoc tribe, not Klamath, raided the camp and killed the three wayfarers.

Regardless, it shows Carson at his best and worst—reliable in battle, but a man with a thirst for vengeance.

Barefoot Across the Desert

Following the Bear Flag Revolt of 1846, an event that’s credited with starting the Mexican-American War, Fremont installed himself as the military leader of California. Soon after, Fremont entrusted Carson with a passel of documents to deliver to Senator Benton and President Polk, giving the two men an idea of the state of play in California.

Carson was making haste to the nation’s capital with the documents when he was intercepted by U.S. General Stephen Kearny, who was operating in New Mexico under the orders of President Polk.

Polk wanted Kearny to chase the Mexican residents out of New Mexico and meet up with forces newly landed in California. Kearny told Carson he needed a guide to San Diego, but the man so loyal to Fremont insisted on rushing to Washington D.C. When Kearny made it clear he was ordering Carson to assist him, the scout relented, trusting a member of Kearny’s army with the delivery errand.

Soon after Carson was requisitioned as a guide, Kearny blundered into a battle near the village of San Pasqual, California.

During the battle, the Mexicans used long lances and swords to injure and kill the American soldiers who were unfamiliar with the terrain and style of fight. A good part of Kearny’s forces were destroyed or badly injured and the general himself suffered serious wounds.

During the fight, Carson—despite never being a member of the U.S. military—performed better than most of his fellow soldiers, recognizing the superiority of the Mexicans’ weapons for close fighting. Instead of rushing into the fray, Carson took cover in the brush and, using his trusty rifle, began picking off rival soldiers with a cold efficiency.

By many accounts, Carson factored largest in ensuring the American army wasn’t entirely routed that day. But Kearny’s army was hurt and outnumbered and taking shelter on a nearby hill.

With water and food running thin, it was up to Carson to save the day. Using the cover of darkness, Carson and two other soldiers removed their boots to sneak past the line of expectant Mexican sentinels. The only problem was the men lost those boots during their escape, meaning Carson was forced to walk 25 miles barefoot across the desert to alert reinforcements about the grave state of Kearny’s army.

“Finally got through, but had the misfortune to lose our shoes,” Carson recounted in his memoirs. “Had to travel over a country covered with prickly pear and rocks, barefoot.”

Carson reached San Diego and alerted the reinforcements, who swiftly rode to Kearny’s rescue just as the general had forsaken hope of salvation.

Thus Carson, despite not serving in the U.S. military, played one of the most instrumental roles in the war that would lead to the incorporation of New Mexico and California while displaying an uncanny knack for putting his stamp on the major events at the dawn of the West.

Civil War

In 1861, Carson began his official military career when the Civil War broke out, joining the Union Army. His official career lacked the heroic glory of his unofficial exploits. After the Union Army suffered defeat at the Battle of Valverde in February 1862—in which Carson led the First Regiment of the New Mexico Volunteers—the mountain man turned soldier rallied the regiment to help repel the Confederate forces, forcing them to flee to Texas in August.

But the experience also segued into the most dishonorable chapter of Carson’s life. Having chased the Confederates out of New Mexico, Carson’s commander, Major General James Henry Carleton, enlisted Carson in his fight against the Apaches, and later the Navajo.

While Carson espoused no love for the Apache tribe, his participation in the Indian Wars of the Southwest was half-hearted. Carson was in his late 40s, battle weary and hobbled by injury.

He attempted to resign his commission, but Charleton refused, ordering Carson to lead the campaign against the Navajo. Carson’s orders included shooting Navajo men on sight while imprisoning women and children.

But the Navajo proved elusive, able to retreat into hiding places scattered throughout their vast territory. So Carson burned their homes, destroyed their crops and killed their livestock.

The Navajo, knowing starvation was imminent if the campaign continued apace, surrendered and Carson marched them to a reservation on a spare site astride the Pecos River.

After the brutal march, Carson returned to Taos, New Mexico—where he lived much of his adult life when he wasn’t rambling through the American West—for the final time.

He had married Josefa Jaramillo, the daughter of a prominent Mexican family living in Taos, and she bore him eight children. She died while giving birth to the last, a son.

Carson, heartbroken, tired and firmly ensconced in his status as a legend of the American West, outlived his beloved wife by only a month. He died at age 58 on May 23, 1868.

According to H.R. Hilton, the doctor who tended to Carson in his death throes, the frontiersman’s last words were “Compadre, adios.”

Carson’s Legacy

Aside from the city, river and pass near Lake Tahoe named after the famous frontiersman, Kit Carson casts a huge shadow over the American West.

While no one disputes his many contributions to the founding of the American West, several modern historians take issue with his attitude toward Native Americans and his role in their subjugations.

They note his lifelong hatred of the Blackfeet, the Klamath Lake Massacre, and the wars against the Apache and Navajo.

But others also point to a more complicated view of Carson’s relationship with the indigenous, noting his marriage to Singing Grass, his knowledge of native languages and his appreciation of their culture and their relationship to the land.

In 1868, months before he died, Carson accompanied several chiefs of the Ute tribe to Washington D.C., where he pled with then-president Andrew Johnson on the tribe’s behalf.

Historian David Roberts sums it up thusly:

“Carson’s trajectory, over three and a half decades, from thoughtless killer of Apaches and Blackfeet to defender and champion of the Utes, marks him out as one of the few frontiersmen whose change of heart toward the Indians, born not of missionary theory but of first hand experience, can serve as an exemplar for the more enlightened policies that sporadically gained the day in the twentieth century.”

Despite the controversy, agreement is near universal that Carson’s courage, resourcefulness, abilities as an outdoorsman and skills as a soldier are not exaggerations. He was the genuine article present for the glory and the pangs attendant at the birth of the West.

Former Tahoe resident Matthew Renda is a Santa Cruz–based journalist and history fan.

No Comments