26 Jul Sugarloaf’s Grand Illusion, Revealed

How a 1979 ascent near South Lake Tahoe changed rock climbing for future generations

Sometimes rules should be broken—especially when ethics, standards and traditions slow the progress of an entire sport.

Tony Yaniro illustrated just how valuable it can be to break rules when in 1979 he conquered Grand Illusion, the most difficult climbing route of that time. His achievement created a massive paradigm shift in American rock climbing, and it all began at Sugarloaf, an unpretentious granite climbing area just outside of South Lake Tahoe.

Kyburz may be a small community but it’s home to world-class climbing, photo by Paul Newton

Sugarloaf’s Great Granite

Sugarloaf is located near Kyburz, a small community along U.S. Highway 50. People driving eastbound spot it when they see a sign that reads, “Welcome to Kyburz. Now leaving Kyburz.”

On the north side of the highway, Sugarloaf hovers above the town. Climbers from all over the world parallel park at a wide spot along the highway just before reaching the sign. They unload heavy backpacks from the trunks of their cars while tourists and commuters speed past. They rifle through their gear making sure they have everything: hardware, slings, ropes, warm clothing, snacks and water. Heaving their heavy loads onto their backs, they wait. The moment there is a break in traffic, they rush across the road and search for a narrow trail leading to Sugarloaf and the Grand Illusion climbing route.

The scenery through the forest is unremarkable at first, but as climbers cross over the Pony Express trail and ascend the mountain, they come upon a cluster of boulders and towering cliffs that make up the climbing area known as Sugarloaf.

Sugarloaf is home to some of the Tahoe area’s highest-quality granite and is known to climbers worldwide as the place where California’s Yaniro conquered the Grand Illusion route. His achievement changed the way future generations thought about climbing.

Assessing the Ascent

Yaniro was 15 years old when he out-climbed veteran John Long at Suicide Rock in Southern California. He looked for a new challenge and, at age 19, found it at Grand Illusion.

Yaniro arrived at the small community along the South Fork of the American River in the winter of 1979. He lugged his heavy pack up the mountain until he reached the east side of the main crag. He stood at the bottom of a smooth, 250-foot cliff with a vertical crack slashing through the slab of granite like a lightning bolt frozen in time. Atop the slab sat a boulder shaped like a giant loaf of bread. The loaf jutted out 60 feet, creating an overhang. Embedded in the overhang was a dihedral, a rock formation shaped like an open book. The dihedral tilts forward at a 45-degree angle and extends upward approximately 85 feet. A thin crack runs through the vertical crease of this book-like formation.

“Granite (unlike other rock) doesn’t form overhanging walls with holds. It’s smooth,” Yaniro says in a 2014 YouTube video titled Rock Climbing Classics: EP#5, which sees Yaniro recollect the line and the era as it is reclimbed by 13-year-old Mirko Caballero.

Yaniro knew traditional rock climbers of his time had never climbed a route that difficult. He wanted to find a way to conquer the route and propel climbing to a higher level of difficulty, even if it would take several tries before making it to the top. He was determined to find a way.

“Twenty years before 1979 there was no such thing as a 5.11. But 5.11 became standard,” Yaniro says. “I just got it out of my head that there was a limit to climbing difficulty.”

Yaniro studied the dihedral to plan which techniques he should use. All the methods he knew and practiced seemed unsuitable at first. Should he use crack climbing techniques or dihedral climbing techniques? The angle of the overhang would be like climbing the inside of a teepee. Its thin crack also meant he had to be strong enough to perform repeated pull-ups with his fingertips.

Yaniro gave up trying to figure out a strategy. He slipped into his harness, tied into the rope and checked he had all the hardware he needed to place anchors in the crack. He would use carabiners to attach his rope to the anchors should he fall. Once everything was set, he climbed.

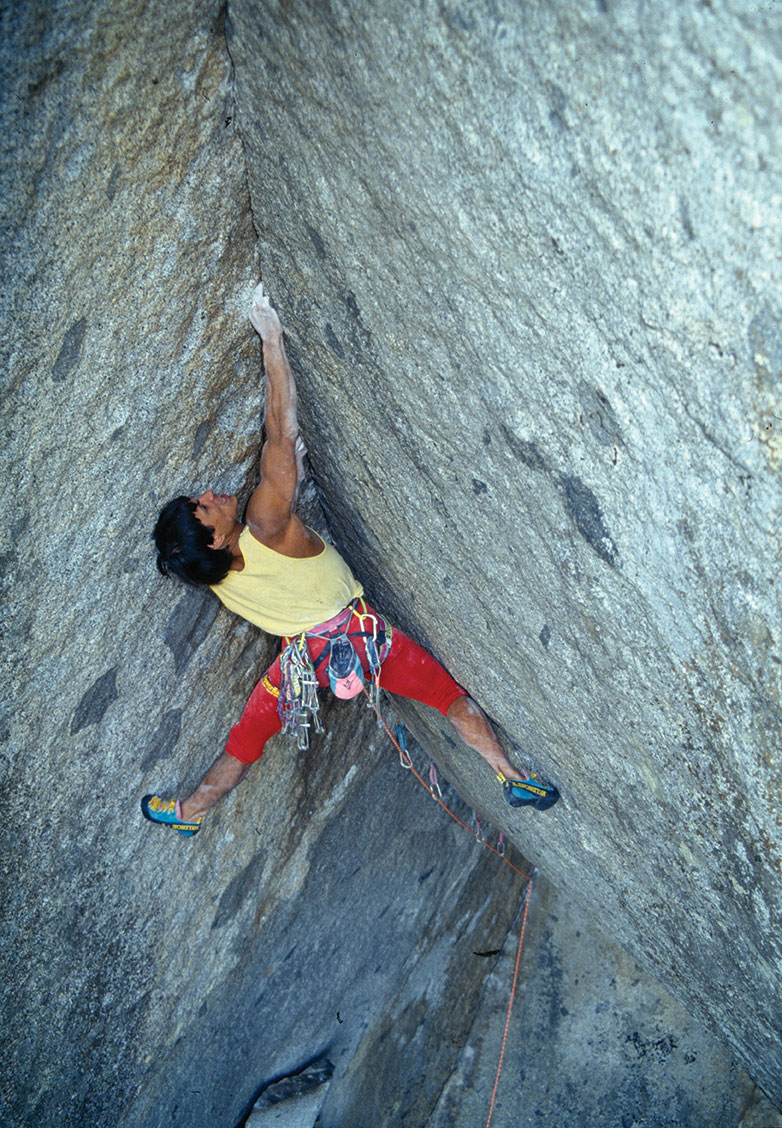

The dihedral formation tilts forward at a 45 degree angle

Ethics of Hangdogging

He placed only a few anchors in the crack before he fell and dangled from his gear like a yo-yo.

Traditional climbing standards and ethics in 1979 dictated that Yaniro not hang on his rope in order to feel for the next hold or study the crack to plan his next move. He was supposed to descend immediately and try again from the bottom. Instead, Yaniro decided to ignore the rules.

He stayed put, and from a dangling position felt the crack above his head to figure out the best place for his hands. He was lowered quickly before anyone saw him—before anyone caught him hangdogging.

“Grand Illusion was my first experiment in hangdogging,” Yaniro says in the Rock Climbing Classics video. “I felt guilty but it was the next step in difficulty. I was going to have to figure something out.”

“Hangdogging,” says Steve Bechtel, a veteran climber and a certified strength and conditioning specialist based in Wyoming, “and replica handholds are tools used straight across the board by all the top climbers in the world today.”

But back then, Yaniro, who was known for mastering routes no one else could ascend, was expected to uphold climbing standards. He should not have even peeked at the crack after falling if he were truly ethical.

Yaniro knew if he found a way to conquer Grand Illusion, he would make climbing history. But how? He refused to give up. He climbed as far as he could a few more times, hung on the rope to feel the crack and memorized the shape of the holds. He then went home and made training devices from wood that resembled the crack. He focused on the specific muscle groups he needed to conquer the climb and used his training devices between attempts.

Yaniro returned to Grand Illusion several times that winter, climbing a little higher before falling and dangling on the rope while feeling for more handholds.

“Yaniro didn’t limit himself to what other people said was right or wrong,” says Caballero, the now-15-year-old athlete who appeared in the same Rock Climbing Classics video.

Hangdogging was the way Yaniro discovered that every single move on Grand Illusion was doable. “If the individual moves were doable,” he says, “I knew I would be able to do the entire climb in one push.”

Yaniro was turning hangdogging into a viable climbing technique.

It was also his first step toward becoming what climber and writer Pat Ament in History of Free Climbing in America called “a leading American pioneer of hold manufacturing.”

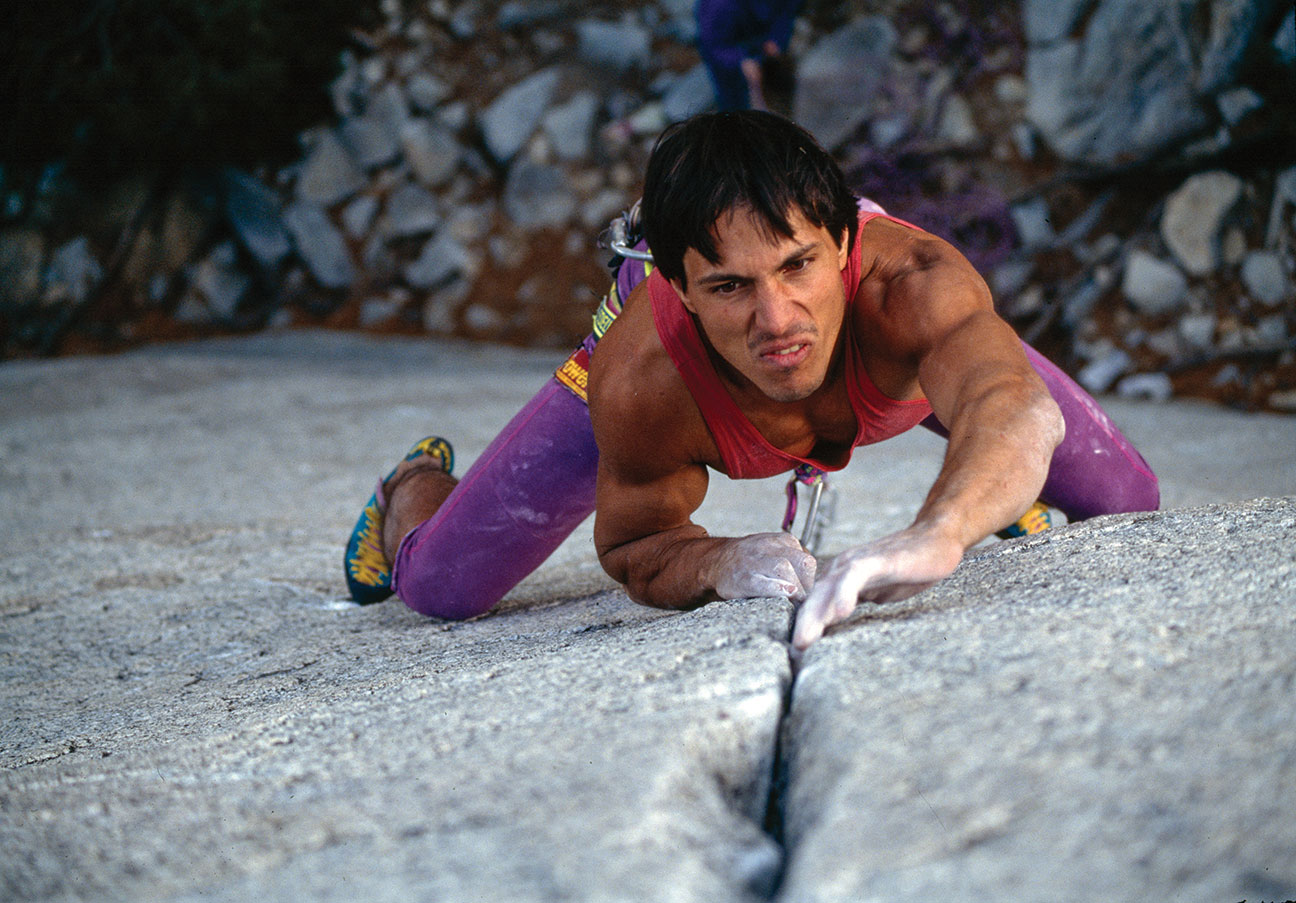

Hangdogging allowed Yaniro to discover that more of Grand Illusion could

be climbed, photo by Heinz Zak

Pioneering a Style

Climbers who noticed how Yaniro was climbing during those early months made fun of him, at first. But, when news of Yaniro scaling the crack at such steep and awkward angles hit the press, the ridicule stopped. He had done it. He had climbed the world’s first 5.13c—the highest grade of difficulty of his time.

If a 5.0 is considered an easy climb for most individuals, and a 5.10 is a climb requiring training, then a 5.13 can only be conquered by extremely fit individuals.

The rules of traditional American climbing standards and ethics changed after that. Climbers realized that hangdogging and practicing on training devices and replica handholds were not such bad ideas, especially if it meant climbers could train to conquer spectacular routes. They learned they could get stronger faster and the grade of difficulty could be pushed to higher limits.

Yaniro, along with other climbers of his time, predicted that during the next 20 years after the first ascent of Grand Illusion, “a 5.13 would become a standard.” He was right.

Wolfgang Güllich, a German climber, completed the second ascent of Grand Illusion using Yaniro’s techniques. Güllich went on to conquer Kanal im Rucken, the first 5.13d in history; Punks-in-the-Gym, the first 5.14a; and Action Directe, the first 5.14d.

Chris Sharma, an athlete dubbed “the best climber in the world” by National Public Radio, was able to complete routes at or above 5.15 because he worked out moves using hangdogging and replica handholds.

“Hangdogging and training on replicas were the major factors in the general improvement in rock climbing,” says Bechtel.

Caballero, who represents the upcoming generation of champion climbers, says he was inspired by Yaniro’s revolutionary mindset.

“He was a pioneer in the sport and, without people like him, climbing would not be what it is today,” he says.

Who knew that a paradigm shift in the way climbers thought about traditions and ethics would result in huge advances in the sport of rock climbing worldwide? Yaniro broke the rules and proved that, sometimes, rules need to be broken.

Deanna Kerr is a California-based rock climber and writer.

No Comments