26 Sep Flight of the Aeronauts

The centuries-old technology of floating in a giant balloon remains an awe-inspiring feat of human ingenuity—and a whimsical spectacle that never grows old

On the scorched, sprawling streets of Las Vegas, a boy on a bicycle looks up from his handlebars to see a hot air balloon soaring low on the horizon. The improbable ball of heat and fabric hovers gracefully in the sky, a complete counterbalance, if not outright contradiction, to the angular aggression of the loud commercial jets carrying thousands of tourists to his home city every day—tourists who come to stare at a screen instead of the sky.

Lifting off in the Hot Air for Hope festival, photo by Anthony Cupaiuolo

Fifteen-year-old Sheldon has adored these elegant aircraft from afar his entire life, and today it’s just him and the balloon. He stops and straddles his bike, balancing its frame as he snaps photos with the camera hanging around his neck. The balloon floats farther away, and he pedals to catch up, one hand guiding the bike, the other pressing the shutter.

Sheldon watches the balloon touch down in the distance and he pedals harder to reach it, his heart pounding with exertion and excitement.

“I’ve never seen anybody pedal a bicycle so hard just to take a picture of my balloon,” the aeronaut says as the boy approaches. He spreads his arms magnanimously. “Would you like a ride?”

In the current era, such a proposition from a strange man in a balloon to a boy alone on a bicycle would almost certainly trigger, at minimum, fearful hesitation, if not an immediate phone call to the police, whose handcuffs would be out quicker than one could say “wicker basket.” But in early-1980s Las Vegas, the permissive culture, while not exactly propelling young Sheldon toward the open arms of the unknown aeronaut, certainly does little to dissuade him.

“Would your parents be OK with it?” the man asks, grasping at the lowest rung of adult responsibility.

Sheldon, who knows his parents absolutely would not be OK with it, responds with the only thing a 15-year-old boy obsessed with hot air balloons thinks to say when offered the chance to ride in one for the first time.

“Yes.”

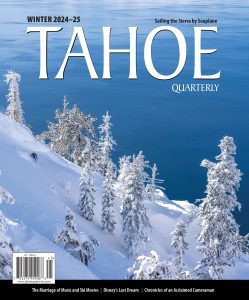

Ballooning Over Big Blue

That brief boyhood ride in a low-flying balloon outside of downtown Las Vegas set Sheldon Grauberger on a path whose journey, more than 40 years later, either validates one’s belief in a random, senseless universe, or deeply undermines it. As for Grauberger, a professional pilot since 2003 with 2,400 hours of flight time and a perfect safety record, he’s content with the destination.

“We had perfect conditions today,” he says over the phone on his drive home to Minden, Nevada, after completing an early morning commercial flight as a pilot for Lake Tahoe Balloons, where he has worked since 2017. The road noise is audible through his car speakers, as is the childlike giddiness in his voice, still evident after all these years. “We went clear back to the base of Mount Tallac, went up above 11,000 feet and shot back out to the lake. We could see all the way to Mount Shasta. It was really, really amazing.”

Minden resident Sheldon Grauberger is a pilot with Lake Tahoe Balloons and a regular participant in The Great Reno Balloon Race, courtesy photo

Lake Tahoe Balloons is the only hot air balloon company in the world to launch and land from a boat, which they do from Lake Tahoe nearly every day between May 10 and October 20. The boat, which is known as the world’s smallest aircraft carrier, follows the balloon as it drifts in the morning breeze, and idles beneath the basket when the ride is done. It bypasses entirely the common need for a chase crew in a pickup truck to trespass on whatever parcel of land the balloon is forced down onto, hopeful that the landowners are delighted by the whimsy of a giant, colorful, deflating sack of air.

“The high mountains around us cause the cold air to be like a bubble over the lake, and it gives us calm air for a longer period of time,” Grauberger explains. “It’s often windy in the afternoon, but in the morning, it’s dead calm, and that’s when we fly.”

Other lake-based hot air balloon operations around the world are eager to develop the same model as Lake Tahoe Balloons, Grauberger says, but the conditions must be perfect: high mountains, predictable winds and a tourist industry robust enough to support the business model. Tahoe has all three.

“This is definitely the easiest place I fly,” he says. “When I fly Albuquerque [International Balloon Fiesta] every year, I have to watch out for power lines, for angry landowners, for radio towers—you name it. Around here, I just have to find the water, and the boat will come to me and make me look good.”

When he’s not flying hot air balloons for work, Grauberger is flying them for pleasure. His preoccupation with flight—one might call it an obsession—is even more noteworthy given his crippling fear of heights.

“I can’t stand on the edge of a building,” he admits, laughing at the irony. “I’m scared to death on a ladder, believe it or not. But you put me in a balloon, I’m just fine.”

Because you’re not physically attached, like a paraglider in a harness, Grauberger explains, and because you’re drifting the same speed and direction as the wind, seemingly motionless, the sensation of vertigo remains dormant.

“You don’t even realize you’re moving,” he says. “It’s a very strange feeling, like you’re a big feather in the air.”

The desire to float like a feather in the air has taken Grauberger to many of the major festivals in the United States as well as several countries around the world, including Mexico and Taiwan, where open invitations exist from local balloon owners for Grauberger to captain their rig. Often, they pay him for the experience; sometimes a new balloon in a new country is all the payment he needs. The passion runs deeper than the paychecks.

Aeronautic Callings

Greg Nelson—Grauberger’s friend, neighbor, mentee and fellow aeronaut—shares the same passion, and a similar origin story.

“I grew up next door to the Kansas City Royals baseball stadium, and the balloons flying at the baseball game would fly over my backyard,” Nelson recalls. “I was just obsessed with them.”

In different eras and different parts of the country, both Grauberger and Nelson fell in love with hot air balloons in childhood, only to bury the quiet passion beneath the deafening roar of real life. College. Career. Family. Homeownership.

But the balloon would not stay down. For his 10th wedding anniversary in 2003, Grauberger’s wife surprised him with a trip to Albuquerque. There, the real estate agent saw a REMAX hot air balloon, returned home to Las Vegas and immediately switched to selling property for REMAX.

“I asked about the REMAX balloon program,” he says, recalling initial conversations with his new employer in the early years of the twenty-first century. “They needed volunteers, and I said, ‘Sure, I’ll do it.’ The pilot was willing to train me for free as long as I didn’t charge him for crewing, and of course I wasn’t going to charge him.”

Greg Nelson, who moved to Minden from Southern California after the pandemic, is part of a growing community of recreational hot air balloon pilots in the Carson Valley, courtesy photo

For Nelson, a graphic designer living with his partner in Los Angeles during the COVID-19 lockdowns, the reality of learning to pilot a balloon was at risk of serious deflation.

“Life stuff kind of got in the middle,” he admits.

The pandemic was the reminder Nelson needed that life is short, and that you can’t learn to fly a balloon trapped in the middle of urban sprawl. An intervention was required.

“I told Chris, ‘I’ve been talking about ballooning for so long—2020 is going to be our year of the balloon.’”

When he started his tentative search into hot air balloon training opportunities, Nelson hit an immediate roadblock: There was no one nearby to teach him. Because of the protected airspace in Los Angeles, the density of the city and the travel distance required to launch a hot air balloon, the opportunities to learn were vanishingly rare.

“In Southern California, the [ballooning] community is way out on the outskirts by Temecula or in the desert outside of Los Angeles,” he says. “No one down there was really interested in teaching me how to fly.”

The more he searched, however, the more one name continued to circulate: Sheldon Grauberger.

“Everybody kept talking about this guy Sheldon,” Nelson recalls. “I got his number, called him and he said, ‘I’m a full-time pilot, I don’t train people to fly. But you should talk to my buddy, Allen.”

Nelson asked if he could get a phone number or email address to reach out and schedule a training.

Laughing, Grauberger informed Nelson through the speaker phone that Allen Anderson himself was sitting in the seat beside him.

“We just got done flying,” Grauberger added.

The connection with Anderson led to frequent trips to the Carson Valley, which resulted in a private pilot’s license—the first step to legally flying a balloon—then a commercial pilot’s license, which is required by the FAA if the pilot ever intends to carry paying passengers or operate for hire. Finally, it became clear that real life was no longer in the city of Los Angeles.

“Chris and I were ready for something different,” Nelson says of the discussions he and his partner had during the pandemic. “We always felt relaxed when we came up here and looked at the mountains and flew balloons. I just thought, ‘Is there some way we could make this work?’ And the answer is, ‘Yes.’”

The two now own a small ranch in Minden, a pickup truck and trailer, and a hot air balloon named Pixel Perfect, which Nelson designed himself and purchased for the cost of a new car.

“You can get an older used one for $10,000 and a new one with lots of features for $75,000,” he says.

“It’s a little bit surprising,” Nelson adds with a laugh. “The city’s been my whole life. But I’m not looking backwards by any means.”

Neither is Chris Coldoff, his partner, though Coldoff wouldn’t mind sleeping in a little later most summer mornings.

“I’m a city boy,” he admits. “I’ve never really been that much into off-roading and stuff like that. Just learning how to drive the trailer and back it up was a challenge, but I feel like I’ve done pretty well at this point. Looking back, I think moving was one of the best things we’ve ever done.”

A Noble Spectacle

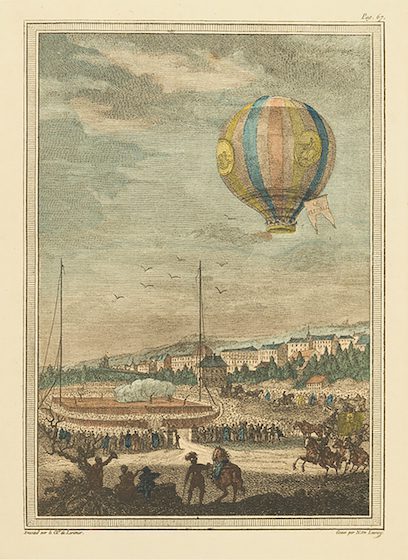

Look way back and the same current of playfulness and passion is evident from the start. Joseph Montgolfier, the elder of two brothers whose family’s successful paper manufacturing business fueled lavish inventor fantasies, called their original hot air balloon prototype of the early 1780s “a cloud in a paper bag.”

This delicate, unlikely cloud was a sensation in pre-revolutionary France, whose monarchy, just years away from public execution, reveled in extravagance.

Within months of launching the first unmanned balloon in Annonay, France—a paper-lined cloth contraption inflated with heat from burning straw and wool, which the brothers called Montgolfier Gas—a royal demonstration was requested. On a cool morning in September 1783, King Louis XVI, Marie Antoinette and the rest of the ill-fated court watched from the lawn in Versailles as a sheep, a duck and a rooster were shepherded into the wicker basket carriage, designed and constructed specifically for this occasion.

There is no record of what was said, but one can imagine the clamor from the royals as the balloon rose 1,500 feet, drifting gently in the mild breeze, the occasional bleat, quack and cluck emerging unseen from behind the tight weave of the wickerwork.

Two miles away, the balloon touched down with a soft bump, the animals disoriented but otherwise unharmed. The flight was a success.

An etching of the Montgolfier balloon ascending in January 1784, image courtesy National Air and Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution

In the days and weeks that followed, flight hysteria consumed France: the royals, the inventors, the adventurers, even the discontented plebeians, whose brewing bloodthirst was temporarily slaked by this new kind of spectacle.

Benjamin Franklin himself, sent by the Continental Congress to Paris to secure support in the American Revolution against England, could not resist carving time from his diplomatic duties to marvel at this burgeoning scientific achievement.

At the first manned flight over Paris in November of that year, just one month after the barnyard expedition, Franklin was asked by a man in the crowd to explain the use of this new technology. He replied, with his trademark wit, “Of what use is a newborn baby?”

Ten days later, in attendance for the historic flight of Jacques Alexandre César Charles and Nicolas-Louis Robert, the first men to launch a hydrogen gas balloon, Franklin expounded on his excitement for the new aeronautical craze sweeping the nation. In a letter to Sir Joseph Banks, president of the British Royal Society, Franklin wrote:

“The morning was foggy, but about one o’clock the air became tolerably clear, to the great satisfaction of the spectators, who were infinite, notice having been given of the intended experiment several days before in the papers, so that all Paris was out, either about the Tuileries, on the quays and bridges, in the fields, the streets, at the windows, or on the tops of houses, besides the inhabitants of all the towns and villages of the environs. Never before was a philosophical experiment so magnificently attended. Between one and two o’clock, all eyes were gratified with seeing it rise majestically from among the trees, and ascend gradually above the buildings, a most beautiful spectacle.”

Banks, in his response, admitted his skepticism about what he initially thought to be a populist fad. “I see an inclination in the more respectable part of the Royal Society to guard against the Ballomania [until] some experiment likely to prove beneficial either to society or science is proposed.”

Undeterred, and seemingly with ample time to defend his newfound love of hot air balloons, even in the final days of the American Revolution, Franklin replied: “When we have learned to manage it, we may hope some time or other to find uses for it, as men have done for magnetism and electricity, of which the first experiments were mere matters of amusement.”

Franklin was correct to see the utility in hot air balloons, which proved invaluable for early discoveries in atmospheric and meteorological science, and continue to fuel research in climate science, astrophysics and radiation studies.

But in the popular imagination, balloons remain, above all, vehicles of excitement and joy.

‘Some of the Best Pilots in the World’

Jean-Pierre Blanchard, a pioneer in aeronautics and the first to cross the English Channel in a hydrogen balloon, brought his show to U.S. soil in 1793, three years after the death of Benjamin Franklin. President George Washington, eager to witness the French novelty firsthand, provided Blanchard with a signed document instructing all Americans to give him aid whenever and wherever he landed.

Blanchard took off from Philadelphia on January 9, 1793, and landed 15 miles and 46 minutes later in Woodbury, New Jersey, presumably to the great surprise of whichever landowner, approaching this ludicrous contrivance, found a proud Frenchman waving a letter bearing the seal of the U.S. government.

In describing the crowd in attendance that day, Dunlap’s American Daily Advertiser, a regional publication, noted “an immense concourse of spectators” whose attention “was so absorbed, that it was a considerable time [before] silence was broke by the acclamations which succeeded.”

The spirit of gathering to admire the spectacle of whimsical flight has changed little in the last 250 years.

Part of The Great Reno Balloon Race, the Dawn Patrol event is reserved for only the most skilled pilots, photo by Lindsay Carroll

The Great Reno Balloon Race is held every September at Rancho San Rafael Regional Park. The world’s largest free hot air balloon event, The Great Reno Balloon Race draws more than 150,000 spectators. The three-day extravaganza, which debuted in 1982 with just 20 balloons, now hosts up to 100 balloons of all colors, shapes and designs, including beloved characters such as Darth Vader and Smokey Bear.

The daily highlight, however, occurs before the day even begins. Dawn Patrol, an assembly of the most skilled pilots, who can navigate in the dark and in atmospheric conditions that change drastically as the sun rises, draws thousands of spectators from their beds before first light.

“We’re probably considered the premier Dawn Patrol in the world,” says Pete Copeland, executive director for The Great Reno Balloon Race. “I know that’s a bold statement, but when you go to Albuquerque—and I love Albuquerque—they basically just get up and they’re gone because of the air currents. Here, the down-sloping air currents let pilots hover above the field and steer their balloons from as low as 100 feet. It’s much better flying conditions for Dawn Patrol.”

This trademark of The Great Reno Balloon Race takes place all three mornings and plays out to choreographed music as the balloons twinkle and glow across the darkened sky.

“We have some of the best pilots in the world flying here,” Copeland adds. “Our local pilots are a really important part of the event, and they’ll tell you this is by far the best Dawn Patrol show they’ll see all year, anywhere in the world.”

Sheldon Grauberger, still as balloon-obsessed today as he was during his childhood in Las Vegas, is one of those rarefied pilots who is qualified to participate in the Dawn Patrol.

The Darth Vader balloon stands out among the beloved characters in The Great Reno Balloon Race, photo by Lindsay Carroll

“There are only about 25 of us in the world that fly in the dark there,” he says. “The announcer has everybody put their flashlights up, and it looks like stained glass, everyone flying around, bouncing into each other. It’s really amazing.”

In addition to Dawn Patrol, where he flies a yellow balloon decorated with purple tulips, Grauberger participates in Mass Ascension all weekend, flying the University of Nevada, Reno balloon, the school his daughter attended and where she currently works as an adjunct instructor. The silver and blue design catches the eye even among a vast horizon of colors and is a fun reminder for Grauberger of why he and his wife moved from Las Vegas to the Carson Valley in the first place.

“We expected her to go to school and then want to come back to Las Vegas,” he says. “She called us one day and she says, ‘Dad, I’m not going back to Vegas. I love it here.’”

The significance of the event is not reserved for world-class pilots only. The spectacle is just as fun for Copeland, who does not come from a ballooning background. Most rewarding for him, he says, and the reason he has served as executive director for the last 15 years with no plans to leave, is the profound sense of community that accompanies the annual event.

“It is so beloved,” he says. “It’s not just hot air balloons—it’s the community. I love seeing the happy faces. That’s what makes it fun and hard to ever want to leave it.”

Ballooning Community

For many aeronauts, community is at the heart of a hobby that some outsiders, like Sir Joseph Banks before them, find a trivial amusement, a mere frivolity. It is the sense of community that ultimately convinced Nelson and Coldoff to make Minden their new home.

“We felt like we couldn’t move here just for the ballooning,” Nelson says. “But we met some great people through ballooning that were becoming friends and who we now consider family—what we call ‘balloon family.’ That’s what drew us here.”

Grauberger, his mentor and neighbor, is at the inner circle of Nelson’s ballooning family.

“It’s a mentorship sport,” Nelson says. “Sheldon is a great mentor of mine. Sometimes if I’m not sure about a weather forecast or if something is feeling funny to me, I can call him, and he’ll be there for me. You know, at all levels, it’s great to have people you can count on.

“You can find your people anywhere,” Nelson adds. “I’m not sure I felt that way before, but yes, you can.”

Crew chief Coldoff, who has developed as rich a community from the ground as his partner has from the air, agrees.

Floating over the Carson Valley in the Hot Air for Hope festival in 2024, photo by Anthony Cupaiuolo

“When we lived in L.A., we were both very focused on our careers,” he says. “We really didn’t have much of a social circle outside of work. Up here, it’s entirely different. It’s all these great people from different walks of life coming together around this one common interest. Everybody is there to pull together and help each other. If you’re at events and you’re a couple people short, you always have people from another balloon come over and help, or vice versa. To me, the community really is the best part of it. Having that kind of extended family, that’s the thing I’ve most enjoyed.”

With the sense of gratitude comes a strong desire to give back to the community—and not just the immediate circle of balloon hobbyists.

Hot Air for Hope started as little more than an informal gathering of aeronauts a handful of years ago. Nelson, eager to connect with his new friends in the sport, shared a post on Facebook inviting local balloonists to show up casually and launch together. The day of the flight, nearly 20 balloons attended, which caught the attention of a local grief and loss support organization called The Center for Hope and Healing.

“What if we did a balloon festival as a benefit for the center?” Nelson remembers Amanda Johnson, the center’s executive director, asking him. “And the festival was born. This past May was our third year, and it’s already become one of the largest tourism draws for Carson Valley.”

For Nelson, now the president of the Carson Valley Balloon Festival board of directors as well as communications director and launch commander for Hot Air for Hope, the festival marries his twin passions for ballooning and community impact. It is not the only program to do so. Nelson also works with schools to educate children about hot air balloons and hopes to eventually develop a curriculum that can expand beyond the Carson Valley.

“We’re always educating to get people more accepting of balloons in the area,” he says. “From kids to adults to local business owners, we try to really touch everybody that we can and just promote ballooning to help it continue in our valley for many years to come.”

The Wonder of Flight

If it is hard to calculate the exact number and demographics of balloonists—their age, race, gender and income level—it is not hard to observe the full scope of humanity impacted by their elegance and beauty, the many millions around the world who stumble out of bed before sunrise just to witness the flight of these unlikely aircraft.

“It’s a childlike type of activity in a way, all the color and whimsy,” says Nelson, who soars year-round in the flight-friendly Carson Valley, accumulating about 50 hours of balloon time annually. “Being around balloons just makes you feel like a kid.”

Balloons take to the sky in The Great Reno Balloon Race, photo courtesy GRBR

Ballooning is an expression of joy and wonder, feelings native to childhood that do not die, but evolve in accordance with the demands of adulthood. Some of us bury our whimsy under a rock; others invite it inside a wicker basket and cut the rope.

“We’re just friendly, fun-loving people,” Grauberger says, with a smile you can almost hear through the phone. “If you’re not friendly, you’re probably not going to enjoy ballooning at all because everybody wants to see you and ask you questions. It’s a very social activity.”

The relevance of hot air balloons in our culture today—scientific achievements notwithstanding—traces a direct lineage to the social origins inherent to the sport from the moment the Montgolfier brothers filled a paper bag with the heat of enflamed wool and set it loose before a crowd into the Parisian skyline.

For social creatures like us, marveling en masse is a spontaneous human response, one that can never truly be suppressed. Despite our profound desires for independence, autonomy and self-possession, every once in a while something comes along to mock our individuality, to compel us to stop, group together and witness in awe.

Michael Rohm is a writer and musician in Portland, Oregon. Benched from ballooning with a broken shoulder, he rehabbed by recording music instead. His band, Token Pony, has a new single now available on all streaming platforms.

No Comments