26 Sep Points of High Interest

Designed and built for one reason—to spot wildfires—lookout towers in the Sierra Nevada also offer intriguing history lessons and fun-filled descents for those willing to put in the work

Below my shoes, the see-through grated steel plank reveals nothing but airspace for what appears to be 1,000 vertical feet. As someone who’s not a fan of bungee jumping or peering over precipices, I feel a twist in my stomach as a awind gust blows me slightly off balance.

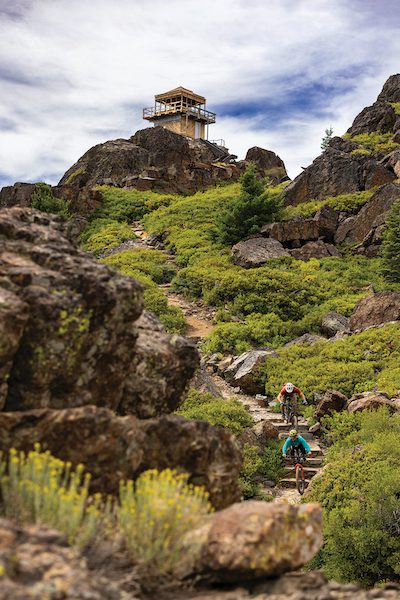

Ken Hanna and author Kurt Gensheimer switch from pedal to walk mode as they ascend the staircase toward the Sierra Buttes Lookout

I grab tightly onto the cold steel railing and calm my vertigo, contemplating how someone could spend every day of their summer perched literally over the edge of this granite monolith—especially in a severe thunderstorm.

We proceed with caution to the top of the staircase and are rewarded with panoramic views from the Sierra Buttes Lookout, where we linger long enough to soak in the splendor of the lofty site before capping the experience with a thrilling descent on our mountain bikes.

Reflecting on this recent adventure, I couldn’t help but wonder: What other fire lookouts in the area have multi-use trails descending from their peaks? Turns out there are quite a few options.

Rich With History

The first fire lookout in California was built in 1876 by the Central Pacific Railroad, which erected a small structure on Red Mountain just below Signal Peak near Cisco Grove.

Amid a building boom during the Great Depression, the Civilian Conservation Corps constructed thousands of lookouts, and by the 1950s there were as many as 5,000 of them spread across the United States. Airplanes and helicopters eliminated the need for most towers by the 1970s, and as a result there are fewer than 300 actively staffed fire lookouts in the U.S. today.

Fortunately, California has the highest number of registered fire lookouts in the country, with 227. There are 25 in the Plumas National Forest alone and more than a dozen in the Tahoe National Forest.

Fewer than half of these local lookouts are actively staffed, but all of them have a unique mystique, from their mountaintop locations to their architectural individuality.

Sierra Buttes Lookout

Although the breathtaking view from the Sierra Buttes Lookout is unlike any other in the Sierra Nevada, ironically, its ultimate demise as a staffed fire lookout was for exactly this reason.

Ken Hanna gazes off into the abyss below the Sierra Buttes Lookout

At 8,590 feet in elevation, and more than 4,000 feet above the Gold Rush-era town of Sierra City, the lookout has such a commanding view spanning from Lassen Peak to the north, Desolation Wilderness to the south, the Great Basin to the east and the Coast Range to the west that it was not effective in triangulating fire starts in closer proximity. That and the tower’s remote location made propane delivery extremely difficult and costly.

The 180 stairs up to the tower are not your traditional stairs; they are a series of aluminum ladders with treads sourced from a military surplus facility. Grass Valley resident Patty Eacobacci has documented the history of the staircase, as her father Richard was a young engineer for the Tahoe National Forest in the early 1960s and worked with Howard Welch to oversee construction of the unique feature, which was engineered primarily for wind load.

To pour the concrete foundations for the stairs, the men drove a World War II 4×4 ambulance that had been modified to carry spring water up to the site. Because the road to the Sierra Buttes was so steep and rough, half the water would slosh from the back of the ambulance by the time they reached the top. Atop the Buttes, they rigged a pulley system with buckets for water transport to the treacherous work area.

Although the lookout was last staffed in 1995, the tower has since become an icon for visitors of the Lost Sierra region.

The Sierra Buttes Overlook trail climbs 1,500 vertical feet in 2.5 miles from Packer Saddle, crossing the Pacific Crest Trail on its way to the fire lookout. Climbing the trail on a bike rewards riders with incredible views overlooking Young America Lake, followed by up to 7,000 vertical feet of descending from the tower to the town of Downieville. This extra-credit approach to the renowned Downieville Downhill is known as the “Tower 2 Town” route, which ranks among the biggest descents in North America.

From the tower, the trail starts with a series of rock stair steps and tight switchbacks, a technical test of rider skill. The trail straightens out a bit as it continues its descent, winding through garage-size granite boulders peppered throughout a beautiful red fir forest. The final mile down to the parking lot has long sight lines along the trail, looking out to the Coast Range and up the shoulder of the Sierra Buttes, where the tiny box that is the fire lookout sits precariously on its precipice.

Pilot Peak Lookout

From the top of Pilot Peak, Sierra Buttes, approximately 30 miles south, looks miniature yet still imposing, with tiny slivers of white streaked on its face—an August indicator that last winter wasn’t as bad as some thought. Pilot Peak also holds ribbons of snow on its north face—a fitting sight given its long skiing history.

Well before there was a fire lookout at the top of the 7,457-foot peak, hardy gold miners in the late 1850s hiked to the top of its steep slopes, streaking down to the high meadow of Onion Valley on 15-foot-long hand-shaped wooden skis. The first known downhill ski races in the Western Hemisphere allegedly took place on Pilot Peak. Some claim they were the first downhill ski races in the world, as the Norwegians hadn’t yet applied their storied tradition of Telemark cross-country skiing to purely downhill pursuits.

The Pilot Peak Lookout at sunset with the Sierra Buttes visible to the south

Pilot Peak stands as a beacon over the rugged and remote beauty of Plumas County, a handful of miles outside La Porte. Its fire lookout is one-of-a-kind: a two-story hexagonal cab with flying buttress supports for the overhang. Designed by U.S. Forest Service architect Robert Sandusky and built in 1976 (the original tower, dating to 1916, was burned by vandals in 1971), Pilot Peak was also the Forest Service’s first solar-powered lookout.

Like the Sierra Buttes Lookout, Pilot Peak is inactive. Unlike the Buttes, however, Pilot Peak is not in good condition. The staircase to the second floor is gone, the roof is missing, and the ravages of winter and summer have taken a toll on this iconic structure.

Access to Pilot Peak lookout from the Quincy-La Porte Road in Onion Valley is about 1.5 miles on dirt, taking the Forest Service 22N84X road and turning on 22N50, which features a series of steep switchbacks to the peak. Recently bladed, the road to the tower is in good overall condition.

Buzzards Roost Ridge

While there is no fire lookout to be found on Buzzards Roost Ridge—a prominent peak and north-facing, backbone-type ridgeline less than 2 miles north of Pilot Peak—there is a recently resurrected trail that’s worth checking out.

Buzzards Roost Ridge plummets more than 3,000 vertical feet in 3 miles to Nelson Creek in the Middle Fork Feather River region. During the Gold Rush, a critically important pack trail ran up this impossibly steep backbone linking the mining camp of Nelson Point with the more established camps of La Porte, Gibsonville and Howland Flat.

Kurt Gensheimer leads the charge with Kacy Roeder close behind down one of the Lost Sierra’s steepest lines on Buzzards Roost Ridge

The Buzzards Roost Ridge trail was lost for more than a century, reclaimed almost entirely by vegetation. But over the last five years the nonprofit Sierra Buttes Trail Stewardship (SBTS) has worked with the Feather River Ranger District of the Plumas National Forest to resurrect the historic route, with work concluding earlier this year.

Perhaps the steepest legal trail you’ll ever ride on a mountain bike, Buzzards Roost is not a casual cruise for a beginner or even an intermediate rider. It’s the double black diamond equivalent of a ski run, with tight, technical and rocky sections off the top, incredibly steep and narrow switchbacks, and a lower half guaranteed to smoke your brakes. For those who love steep, technical trails, Buzzards Roost is an instant classic.

For those seeking a less harrowing trail experience, the 2-mile stretch from the trailhead on Quincy-La Porte Road to the peak of Buzzards Roost Ridge is much more agreeable, a gently graded trail running up the shoulder of the ridge with beautiful views of the Pilot Peak Lookout and Onion Valley.

Babbitt Peak Lookout and Badenaugh Canyon

Babbitt Peak, the highest point in the Bald Mountain Range at 8,760 feet, straddles the border between the Tahoe and Humboldt-Toiyabe national forests about 8 miles southeast of Loyalton. The ridge provides an ideal location for a fire lookout, boasting 360-degree views from Sierra Valley, Stampede Reservoir and the Truckee region all the way to the Sierra Crest, Mount Rose Wilderness, Peavine Mountain, Reno and Cold Springs.

Constructed in 1929, the Babbitt Peak Lookout stands out with its “dunce cap” design featuring a steep roof pitch. Babbitt is one of the only remaining lookouts of this style, and is also one of the few active lookouts in the Tahoe National Forest, with a full-time Forest Service employee working and living in it from late May through October.

Kacy Roeder descends the footpath from the Babbitt Peak Lookout

Just off the western shoulder of Babbitt Peak is the entrance to Badenaugh Canyon trail, which was established around the same time as the fire lookout and was used by hikers, horses and mountain bikes until the Cottonwood Fire in 1994 burned 49,000 acres in the Bald Mountain Range. Although the Babbitt Peak Lookout was spared, the western face of the mountain, including Badenaugh Canyon trail, was severely burned.

The trail was abandoned as a result, and the chaparral that grew in place of the tree cover rendered it impassable for nearly 30 years. About five years ago, a Tahoe National Forest hotshot crew out of Truckee spent weeks with chainsaws reopening the trail corridor, and a couple of years later SBTS, along with volunteer help from Truckee Dirt Union, conducted weeks of finish work to reopen this historic route linking Badenaugh Canyon Road up to Babbitt Peak.

Dropping 2,200 vertical feet in under 3 miles, Badenaugh Canyon, nicknamed “Rad-n-Raw” for its characteristically

old-school feel, is incredibly steep and rather technical. The top third of the trail winds through a loamy old-growth forest, with tree trunks sporting thick jackets of electric green moss. It then opens up into the old burn scar, with sweeping views of Sierra Valley and the Sierra Buttes in the distance. But don’t get distracted by the views, as the trail continues to plummet into technical rocks and a 30-foot-long, steep, rideable rock slab before mellowing out into a fast, flowing bottom third to the finish.

Perhaps the only downside of Badenaugh Canyon trail is where it finishes. To get back out to the main Smithneck Road, you either have to make a right and head north down the rocky and bumpy Badenaugh Canyon Road toward Loyalton, or make a left and climb 300 vertical feet before descending the last 800 feet on a dirt road to Smithneck—not the best finish to an otherwise incredible trail experience.

Understanding this reality, SBTS recently flagged a proposed 2-mile addition to Badenaugh Canyon trail, crossing the road and traversing to the next ridgeline for a final 1,000-vertical-foot singletrack descent to Smithneck Road, where it will plug into the existing Boca-Loyalton trail. This future connection will make Badenaugh Canyon a 5-mile, 3,200-foot descent and a proper shuttle-capable trail similar to other, more popular, fire lookout trails in the area—including Mount Hough and Mills Peak. SBTS hopes to complete this extension in the next five years.

Argentine Rock Lookout

Perched beautifully on the edge of a cliff on Grizzly Ridge near Quincy, Argentine Rock Lookout was built in 1934 and remained active until 1980. Forty years later, the Forest Fire Lookout Association (FFLA), a nonprofit dedicated to preserving lookouts and their legacies, applied for a federal grant to restore the 11-foot enclosed tower with a C-3-design cab and catwalk.

Kacy Roeder and Kurt Gensheimer descend a trail of rock steps from the Argentine Rock Lookout

FFLA sent representative Chris Rivera to Quincy to assemble a team of volunteers to help with the work. Plumas County resident Jeff Greef stepped up to the challenge, taking over as chairman of the Argentine Rock Lookout Group. Greef leads the construction efforts, which began in 2023 by hiring a contractor to truck in 25 loads of gravel to improve the road up to the lookout.

The last couple of summers the group has focused on pouring concrete, fabricating a steel staircase to the tower over large gaps in the rocks, building a wooden staircase to the second floor and extensive carpentry work, including custom windows.

“The biggest challenge with this project has been getting volunteers to show up,” says Greef. “Although the dirt road up to the tower is in good shape, it takes more than an hour to get up there from Quincy, and you can only really work four hours a day.”

Although there is no trail from Argentine Rock, the dirt road descends 3,400 vertical feet from the tower to Highway 70. For gravel bike enthusiasts who want to explore the Lost Sierra and find some long, fast and flowing descents with drop bars, the Forest Service 25N29 to 25N42 road, with views of Argentine Rock Lookout, is one of the region’s best downhills. The 401 county road up Squirrel Creek from the highway before turning into 25N42 is also a good climb, never too steep or rocky.

The plan for Argentine Rock is to turn the lookout into an overnight rental for the public, much like the Calpine and Sardine Peak lookouts. A growing number of adventure motorcyclists are becoming aware of the lookout as well thanks to the recent release of the California Backcountry Discovery Route.

Fire lookouts have a fascinating history in the American West. Many of these strategically located and designed lookouts are still being used today, and others that have fallen into disrepair are being restored as recreational assets—often paired with new and old trails leading from their peaks.

Kurt Gensheimer is a Verdi resident with 20 years of freelance writing experience. His latest venture, Mind the Track podcast, celebrates singletracks in summer, skintracks in winter and mountain culture in the Tahoe region.

Learn More

For more information about the history of lookouts, visit the Forest Fire Lookout Association.

To help with the restoration of Argentine Rock, contact Jeff Greef at kapterian@gmail.com and follow the progress on Instagram at @argentinerocklookout.

No Comments