30 Sep Snow Stars

Tahoe’s slopes were hallowed terrain during the height of ski and snowboard filmmaking

Mecca, as defined by Merriam-Webster, is “a place regarded as a center for a specified group, activity or interest.” In a nutshell, that was Tahoe in the heyday of ski and snowboard filmmaking.

The reasons are many. Aside from its unequivocal beauty, Tahoe featured the perfect medley of ingredients for filming winter sports. Steep, easily accessible terrain. Prodigious snowstorms followed by bright, sunny days. Athletes as daring and competitive as they were talented. Squaw Valley. Donner Summit. Cliffs. The list goes on.

Although these elements remain, Tahoe is not the filming hotbed it once was. That’s not to pick on Tahoe. The area will forever hold its own with the best winter playgrounds on earth, and still produces quality ski and snowboard footage.

The truth is that the ski filmmaking industry as a whole is not what it used to be, while snowboard film companies have nearly died off altogether. There are a handful of factors, but the primary culprit can be summed up in a word.

“Internet,” says Mike Hatchett, co-founder of Tahoe-based Standard Films, which reigned as one of the top snowboard film companies from the early 1990s until its final video in 2012. “The Internet enabled people to get instant gratification with three-minute web edits. Back in the day, people snowboarded all winter and then had to wait until September to catch the premiere or buy the VHS or DVD, and they were totally pumped.”

Scott Gaffney, a Tahoe City resident and director of Matchstick Productions (MSP), one of skiing’s premier filmmaking companies, agrees. “Now there are 20 edits dropping online a day with sick ski footage. It changed the whole dynamic of watching ski movies,” he says.

Combined with digital video cameras available to the masses, fewer sponsor dollars and an over-saturation of content, the filmmaking industry has taken an undeniable hit.

Nevertheless, the major players (Warren Miller Entertainment, MSP, Teton Gravity Research, Absinthe Films) continue to push the boundaries in the face of this downturn. And no matter what the future holds, Tahoe will always boast a rich history of ski and snowboard filmmaking, with athletes and cinematographers who were second to none in terms of progressing their respective sports.

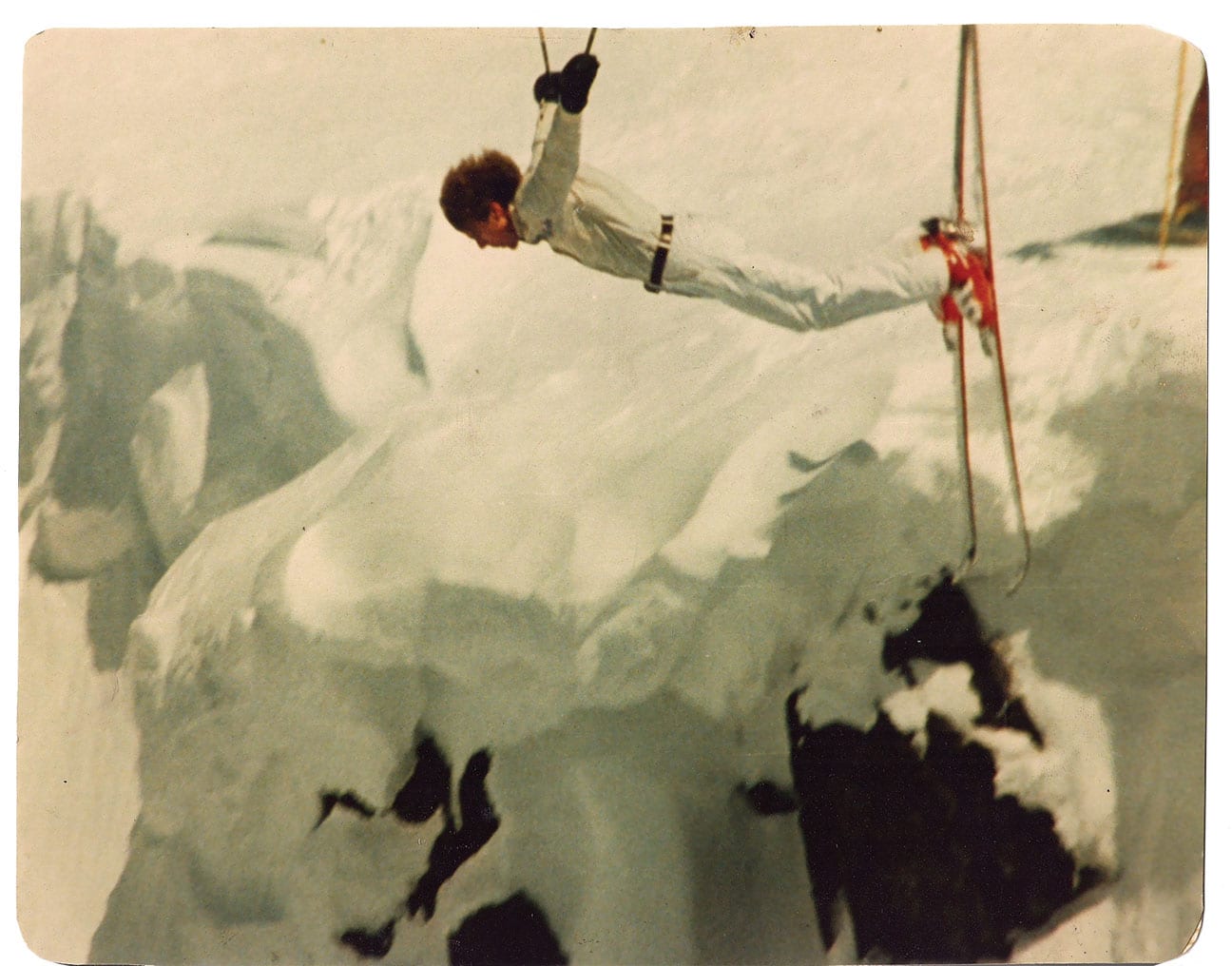

Tuck Rivard in a scene from Daydreams, photo courtesy Craig Beck

Tuck Rivard in a scene from Daydreams, photo courtesy Craig Beck

Seminal Films

Warren Miller, regarded by many as the godfather of ski filmmaking, released his first film, Deep and Light, in 1950. But ski movies can be traced back to the early 1930s in Germany, when Arnold Fanck wrote and directed films such as The White Ecstasy. Other early ski film producers who predate Miller include Otto Lang, John Jay and Dick Durrance, while Dick Barrymore threw his hat in the ring with the 1962 release of Ski West, Young Man.

But for all intents and purposes, it was Miller who popularized ski films by touring and narrating his movies annually at venues across the country. Minus Miller’s narration—Jonny Moseley now voices Warren Miller Entertainment movies—the tradition continues to this day.

“I totally grew up on Warren Miller films,” says Eric DesLauriers, who, after seeing childhood friend Tom Day appear in a Warren Miller movie, moved from Vermont to Squaw Valley in the late 1980s to pursue a ski career.

Nearly two decades prior, North Lake Tahoe resident Craig Beck and his crew of skiing friends helped pioneer the budding extreme skiing culture fostered at Squaw Valley.

Beck grew up learning the craft of filming. As an adult, he dove into ski filmmaking in the early 1970s, aiming a Super 8 film camera at his friends ripping around Squaw Valley. He turned the footage into a short video called Timepiece and showed it at the Squaw Valley Racquet Club on weekends. That led to a film project with Canadian Mountain Holidays founder Hans Gmoser, which prompted Beck to step up to a better-quality 16-millimeter film camera.

He continued to gather footage, both in the Bugaboos of Canada and at Squaw. His posse, which included friends Mark and Tuck Rivard, the late David Burnham and Beck’s brother, Gregory, among others, were ahead of their time, jumping and flipping off cliffs at Squaw Valley and Alpine Meadows.

“We were jumping off of everything,” Beck says. “The Vietnam War had just ended and everyone was kind of crazy and happy to be alive. So I started filming the stuff, and we just kept doing crazier and crazier things.”

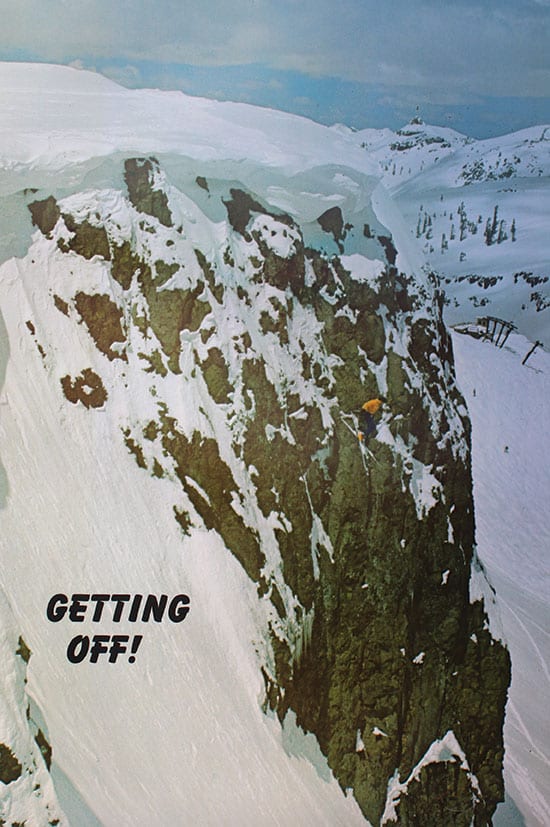

Mark Rivard throws a giant front flip off the Palisades at Squaw during the filming of Daydreams. He broke both of his legs on the landing, photo

Mark Rivard throws a giant front flip off the Palisades at Squaw during the filming of Daydreams. He broke both of his legs on the landing, photo

courtesy Craig Beck

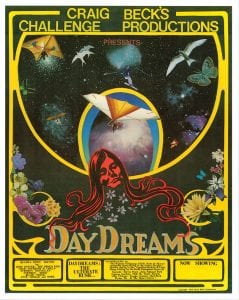

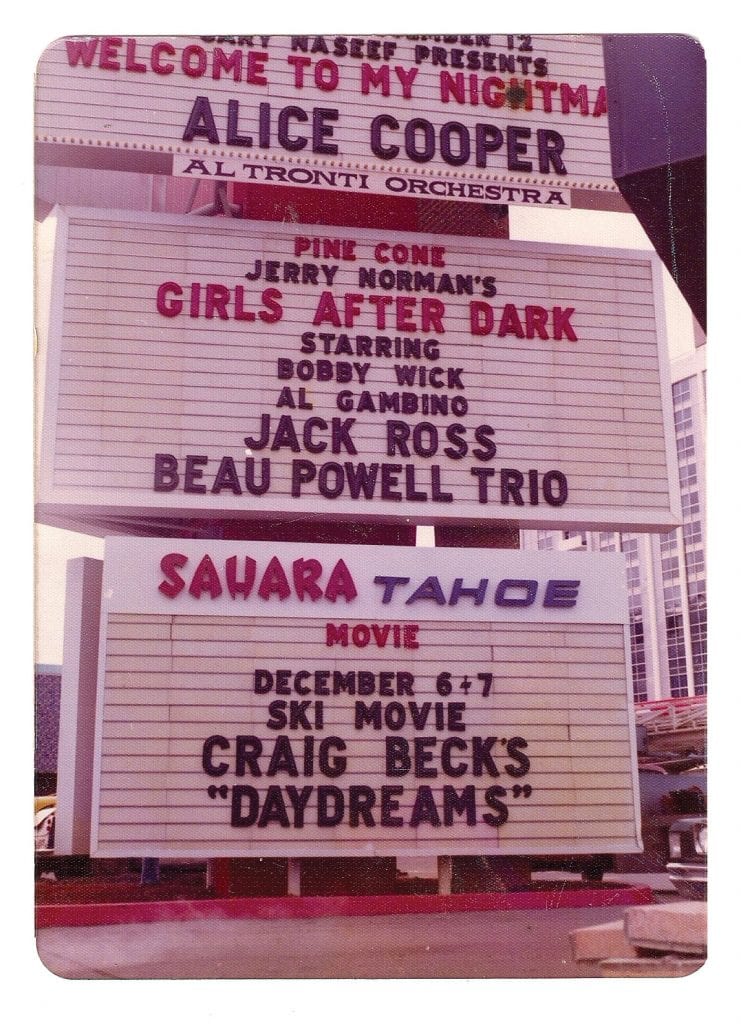

Beck edited the footage in his living room—a painstaking endeavor in the mid-1970s—and created Daydreams, released in 1975. The film was groundbreaking, featuring big airs and daring stunts, as well as a musical soundtrack, limited narration and an artsy vibe.

During a three-day stretch of filming in April 1975, Beck captured footage of his brother, Mark Rivard and Burnham launching off the Palisades, the prominent cliff band atop Squaw Peak. Gregory Beck and Burnham both avoided serious injury, but Rivard, who threw a giant, slow-rotating front flip, broke both his legs upon impact of the drop, which measured anywhere from 80 to 100 feet. The nose of the Palisades is now known as Beck’s Rock in honor of Gregory Beck’s 117-foot jump the previous day.

“In the old Warren Miller movies, the action was there, and occasionally they might have had some big jump or something, but in Daydreams, almost every shot was a ‘wow’ shot,” says Day, who skied in Warren Miller movies in the mid-1980s before becoming a cinematographer.

Beck’s Rock on the Palisades at Squaw Valley was named after this 117-foot drop by Gregory Beck

during the filming of Daydreams in 1975, photo by Tim Weakley, courtesy Gregory Beck

Beck successfully toured Daydreams across the western U.S. and Europe. But after Burnham was killed by a drunk driver, Beck ended his film tour.

“David’s death was a serious blow. It really knocked me off my feet for about six months,” says Beck, who named one of his children in his friend’s honor.

Because VCRs had yet to gain mass market appeal, Daydreams never reached the level of fame as later extreme skiing films.

“I converted it later to VHS and was really unhappy with that, because the way it was presented in theaters, it had such vibrant colors, and then to see it like that just sucked,” Beck says.

Daydreams shares billboard space with Alice Cooper at Sahara Tahoe, photo courtesy Craig Beck

The Schmidt Influence

In 1979, a downhill ski racer from Montana named Scot Schmidt followed the advice of his coaches and moved west to Squaw Valley. He was impressed from day one.

“It was pretty loose,” Schmidt says of Squaw. “Steve McKinney and Paul Buschmann and all the longhair speed skiers were running around like crazy, dropping into the Palisades and practicing their speed-skiing tucks. I was blown away. Coming from Bridger [Montana], which was a tight, scrappy, technical mountain, and then going to Squaw, which is big, open and fast, it was totally different. So the first time I saw those guys, I ran down and got my 220s and was on them the rest of the season.”

Scot Schmidt, shown dropping into Eagle’s Nest at Squaw Valley, was perhaps the biggest name to emerge from the resort’s

early extreme skiing era, photo by Gregory Beck

Schmidt says he soon fell out of racing after growing frustrated with the sport and running into money issues. But that wasn’t a bad thing. He had quickly adapted to Squaw’s sprouting extreme skiing scene, making a name for himself by tackling some of the resort’s burliest terrain with the fluid style that would define his career. His exploits caught the eye of a Warren Miller cameraman in 1983.

“So then I got a letter from Warren Miller basically inviting me to travel around the world with his film crews,” says Schmidt, who appeared in Miller’s 1983 movie Ski Time. “That was actually the first ski film I ever saw. I had worked with a cameraman, but VCRs weren’t big yet, and I grew up in Montana where we didn’t have the Warren Miller tour. It just didn’t exist.”

Schmidt went on to star in eight more Warren Miller films over the next decade, and some 45 ski movies total in 25 years of filming. He brought his friend, Day, along for the ride.

“Warren Miller wanted to come film Scot in Squaw and they wanted a couple more skiers, so they asked him who he wanted to ski with, and he asked me,” says Day, who made his film debut in Warren Miller’s Ski Country in 1984.

Day, who still resides in Olympic Valley, made the transition from skiing to filming in the late ’80s and is still regarded as one of skiing’s elite cinematographers for Warren Miller Entertainment. Schmidt now splits his time between Santa Cruz and Big Sky, Montana, where he serves as the Yellowstone Club’s ski ambassador.

Despite spending over 100 days a winter on the slopes of Montana, Schmidt says he will always hold Squaw in high regard. After all, one of the hairiest lines on the Palisades—Schmidiots—received its moniker after he skied it to perfection on film.

“Even to this day, I gauge everything I do by what I learned on the Palisades back then,” Schmidt says. “Every year it’s different. Some years it’s easy, and some years it’s really not.

A young Scot Schmidt takes flight at Squaw Valley, photo by Gregory Beck

Blizzard of Aahhh’s

Warren Miller might have given Schmidt his break into filming, but Greg Stump made him an international star. At the same time, Stump, an East Coast freestyle skier turned filmmaker, exposed extreme skiing to the mainstream with his 1988 release of Blizzard of Aahhh’s.

“Greg really put the whole ski movie business on its ear with Blizzard of Aahhh’s,” says Schmidt. “That film overnight did a lot for everybody involved, including myself. It was just so well received and progressive.”

Although Warren Miller’s Ski Time was the first film that fired up a young Scott Gaffney to eventually move to Tahoe, Stump’s blockbuster hit is what motivated him to pursue ski filmmaking as a profession.

“A thousand people have said it, but Blizzard of Aahhh’s is what changed my life,” says Gaffney, who was raised in upstate New York. “I remember walking out of my first viewing of that and being like, ‘OK, this is what I’m gonna do.’ It showed a whole different level of skiing, but it was more than that, too. It showed freeskiers pursuing a way of life rather than just something to do.”

The film thrust another Tahoe skier, Glen Plake, into the spotlight. Tagged as a rebellious “bad boy” in the film, Plake was a Heavenly-based freestyle skier who stood out with his spiky, sometimes multi-colored, foot-long Mohawk. Aside from his radical hairdo, Plake could flat-out ski, which he showcased with his performance in Blizzard of Aahhh’s.

“Stump gets credit for pairing the odd couple, but it just kind of happened,” says Schmidt, whose low-key personality contrasted with Plake’s flamboyant style. “We had good chemistry, and it worked.”

Stump’s crew filmed a portion of the movie at Squaw before heading overseas to Chamonix, France, where Plake, Schmidt and Seattle’s Mike Hattrup displayed their skills on the famously burly terrain of the Alps.

Rob DesLauriers shows off his impeccable control during the filming of Eric Perlman’s Skiing Extreme IV in 1991, photo by Eric Perlman Productions

Rob DesLauriers shows off his impeccable control during the filming of Eric Perlman’s Skiing Extreme IV in 1991, photo by Eric Perlman Productions

Skiing Extreme

Around the same time, longtime Truckee resident and world-traveling climber, skier and filmmaker Eric Perlman was documenting some of the most riveting skiing action of the era with his aptly named Skiing Extreme videos.

The film series—six in total released between 1988 and 1993—featured an array of local talents, including Schmidt, Day, the DesLauriers brothers (Eric and Rob), John Tremann, Terry Cook, Kevin Andrews and more. Craig Beck was a cinematographer on the first two films, which were a hit from the start.

“Skiing Extreme I was just 22 minutes. But we sold a ton of them—like 22,000—which doesn’t sound like much, but back in the day, people were willing to pay $17.95. And it was all VHS, so suddenly the doors were ripped open, and the Warren Miller guys were pissed because we outsold them,” says Perlman, adding that Skiing Extreme II was expanded to 40 minutes, and the next four were between 48 to 52 minutes.

Although Perlman’s band of skiers traveled to iconic locations around the world, most of the footage was shot in their backyard—places like Donner Summit, Squaw Valley, Alpine Meadows and Mount Tallac.

Terry Cook throws a front flip at Alpine Meadows while filming for Skiing Extreme II in 1989, photo by Eric Perlman Productions

Terry Cook throws a front flip at Alpine Meadows while filming for Skiing Extreme II in 1989, photo by Eric Perlman Productions

During one particularly eventful day of filming on Donner Summit for Skiing Extreme IV, Eric DesLauriers recalls his brother getting swept off a cliff band and buried below.

“He was upright,” he says, “but the snow came over the top of him, and he punched his hand up to create an air path. So John Tremann came down, dug him out, hiked back up, and jumped a 135-footer. That was the first time anyone had filmed anything that big.”

Actually, says Perlman, Tremann’s cliff drop measured 140 feet, which was then a world record.

“It was off the tallest rock there at the ASI cliffs. I pulled out a climbing rope and measured it off from the launch point to the impact crater. So it was a genuine measurement,” Perlman says. “Chuck Patterson actually went back and I filmed him doing it too, but he lost a ski on the landing. Tremann landed on his shoulders, but he skied out eventually. That was a good day because we pushed the limits and nobody got hurt.”

Skiing Extreme producer and director Eric Perlman stands by a climbing wall he built on the side of his Truckee

home, photo by Sylas Wright

Different Times

During that era, the average skier stuck to the groomers. The deep stuff, meanwhile, was left for the elite to shred. It was an ideal situation for filmmaking.

“There just weren’t that many people who could ski powder back then, so we had the powder as long as you wanted to keep hiking and looking for it,” says Beck, whose crew used to boot-pack up the mountain, camera equipment and all, when the lifts were closed. “There was so much stuff that was wide open. It provided for a lot of really pretty powder shots.”

DesLauriers has fond memories of those days. Fresh after a storm, he says he and his filming friends could take several “warm-up” runs in the morning before hitting the prime terrain for the cameras. Now, powder at Tahoe resorts gets gobbled up in short order. It’s one of the reasons Tahoe is no longer a coveted location for film crews.

“It’s a tough place to shoot now,” says Gaffney, who commonly filmed for MSP around Tahoe in the 1990s and into the 2000s—namely at Squaw, and with friends such as JT Holmes, Kent Kreitler, Ingrid Backstrom and the late Shane McConkey, among others. “There are so many good skiers here, they just assault the lines in no time. And when it takes a while to set up a camera and get the right angle or whatever, the lines just get slayed right in front of your face.”

The advent of the modern fat ski, which can be traced to McConkey’s creation of the Volant Spatula in the early 2000s, contributed to the shortened lifespan of fresh snow at Tahoe resorts. Snowboarding is also responsible.

“I know there were ideas of fat skis before snowboarding came out,” says Day, who also shot with Standard Films throughout the 1990s. “You take a look at what Shane McConkey did with the Spatula, it’s almost like an identical ski to what the Chinese were skiing on well over a thousand years ago. But, I think it took snowboarding to kind of kick the ski industry’s ass to progress. It showed the possibilities of riding on top of the snow instead of in it.”

The late Noah Salasnek shows off his style outside the Standard House in Agate Bay while filming TB2–A New Way of Thinking, photo by Sean Sullivan

Snowboard Filming Boom

It was only natural for Tahoe to become a hub for snowboard filmmaking, for all the same reasons ski filming blossomed. But it didn’t happen immediately.

Although the sport was gaining traction in Tahoe as early as the late 1970s, it wasn’t until nearly a decade later that the larger resorts allowed snowboarders on their lifts. That’s when the film companies began to emerge. Jerry Dugan and Arthur Krehbiel, who together created Fall Line Films, ignited Tahoe’s snowboard filming boom when they released The Western Front in 1989.

“We all grew up on Warren Miller and Greg Stump, and so when Squaw opened up to snowboarding, someone said, ‘Dude, we could make a movie,’” says Dugan, who had already been filming some of Tahoe’s top snowboarders, including Damian Sanders, Dave Seoane and the late Noah Salasnek.

Fall Line Films released Snowboarders in Exile the following year. The film reached a larger audience than The Western Front and showed the sport’s rapid progression, highlighted by Sanders, Seoane, Chris Roach and Steve Graham shooting off cliffs and performing stylish, skate-inspired tricks. After years of relative obscurity, Tahoe’s snowboarders were suddenly cast into the spotlight.

Brothers Mike and Dave Hatchett, meanwhile, teamed up with Pat Solomon, Shawn Farmer and Nick Perata to produce Totally Board in 1991 under the name Fusion Films. Mike Hatchett also worked with Fall Line Films on two movies, Critical Condition (1991) and Riders on the Storm (1992).

The Hatchetts and Mike “Mack Dawg” McEntire then combined to form Standard Films, which released TB2–A New Way of Thinking (1993), TB3–Coming Down the Mountain (1994) and TB4–Run to the Hills (1995). McEntire then broke off on his own as the Hatchetts continued the TB series.

Like the ski film companies, Fall Line and Standard captured a significant amount of footage inbounds at Squaw. They also hiked for their shots in various locations around Tahoe. The Standard crew even opened the door to some fresh terrain on Donner Summit, including a filming hotspot tucked just off Interstate 80 that they named New Donner, which features a sizable cliff dubbed the I-80 drop.

Andrew Crawford at New Donner in a scene from TB9, photo by Sean Sullivan

“We moved over to New Donner because I wanted to film the steeps,” says Mike Hatchett. “Tom Burt and my brother were totally obsessed with the morning light. There’s that light that happens for like three hours in the morning in Tahoe, from sunrise until about 10:30. I liked how steep the terrain was and how many good angles there were. You could set up on one peak and shoot over to the next peak. So we shot a lot there.”

While many of the riders were either from Tahoe or had moved there because of the burgeoning scene, others visited from out of the area to film with Standard—talents like Johan Olofsson from Sweden and Terje Haakonsen from Norway, who would show up at the Reno airport and call Mike Hatchett for a ride. Oftentimes, the home that the Hatchett brothers rented in Agate Bay, known as the Standard House, would be filled with pro snowboarders in town for a film shoot.

“Many a snowboarder slept over while waiting to film and ride Squaw. Noah [Salasnek] used to sleep under the ping pong table,” says Mike Hatchett.

Terje Haakonsen was one of many snowboarding stars who worked with Standard Films, photo by Sean Sullivan

Dying Breed

As snowboarding grew in popularity, the number of film companies expanded exponentially from the mid-1990s through the mid-2000s, both in Tahoe and beyond. Then they started fading from the scene.

“The market totally got over-saturated, and then the money dried up coinciding with the [Great] Recession,” says Dugan, whose Fall Line Films now specializes in TV commercials and branded content production. “The sponsorship dollars condensed. And the other thing is the way we view content changed.”

Day says another reason for the decline in filmmaking is simply that it’s not easy to produce a full-length movie.

“You have to go out and raise money and produce something that people are going to be stoked about, and that’s hard to do year after year,” he says. “I can speak for Warren Miller. We just finished 68 years in a row of making a ski movie. The simple thing of coming up with a name after that many years is tough.”

Mike Hatchett is still involved in film. He does independent contractor work and is currently filming a travel adventure TV series with Teton Gravity Research called Locals. He says if he could raise the funds and work with the right crew, he’d consider producing another snowboard film.

Gaffney filmed extensively in Tahoe for the first time in six years this past winter for MSP’s latest movie, Drop Everything, which releases this fall. The movie features MSP’s typical lineup of Tahoe-based pros—Cody Townsend, Elyse Saugstad, Michelle Parker—but Gaffney also made a point of showcasing the area’s rising talents in Connery Lundin, Xander Guldman, Ross Tester, Jared Dalen, Josh Gold, Josh Anderson and others.

“There are going to be a whole bunch of Squaw locals,” he says. “I’m trying to show the underground talent that’s here.”

While the golden age of filmmaking is a thing of the past, Gaffney is confident that ski films will endure.

“Fortunately, we still have a loyal crowd who like getting together at premiere stops and checking it out and getting fired up for the winter,” he says. “The Internet has had a major impact, but I don’t think that stoke for watching a ski movie on a big screen is ever going to completely go away.”

Tahoe Quarterly editor Sylas Wright has fond memories of popping a new snowboard film in the VCR and marveling at the action—then watching it again and again.

No Comments